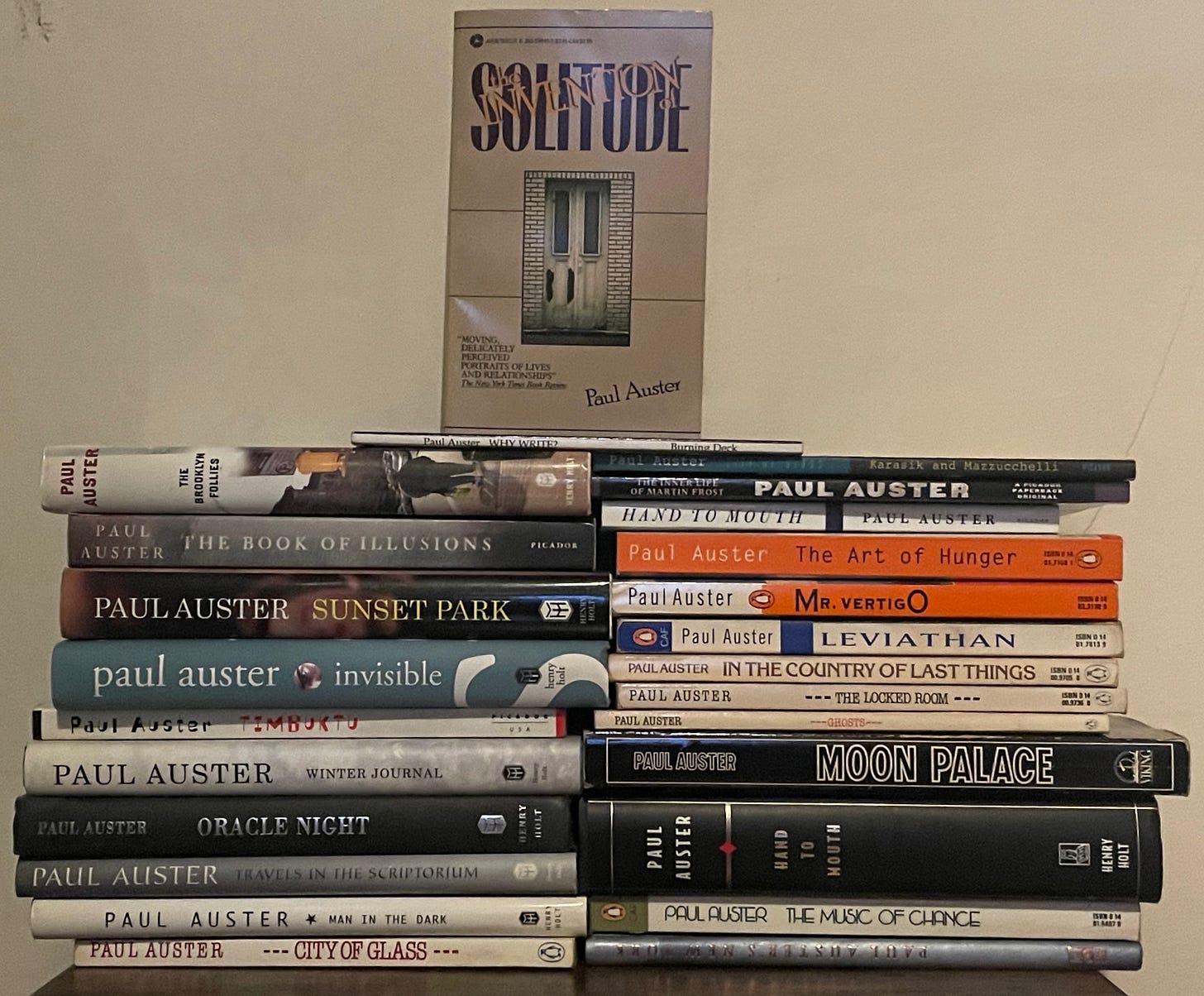

The Invention of Solitude stands at the top of my Paul Auster collection (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

I might not have become a writer were it not for Paul Auster, who died on April 30 at the age of seventy-seven.

Shortly after reading his 1985–86 New York Trilogy — City of Glass, Ghosts, and The Locked Room — I picked up his 1982 memoir, The Invention of Solitude, the first part of which, “Portrait of an Invisible Man,” is about the sudden death of his father in January 1979 at the age of sixty-seven. Auster and his father, Samuel, had many issues and were distant; Paul wrote, “We were fixed in an unmoveable relationship, cut off from each other on opposite sides of a wall. . . . Like everything else in his life, he saw me only through the mists of his solitude.” When Samuel was an infant, his mother shot and killed his father, and she was acquitted on the grounds of temporary insanity. It was a family secret that Paul and his cousins only found out about as adults.

My father, Michael, died suddenly in 1985 at the age of forty-seven; we had a fantastic, loving relationship, with no issues or problems, and my paternal and maternal grandparents were fine, upstanding people with nothing hidden in their closets. Yet reading Solitude and witnessing Auster’s grief still provided much-needed solace for me.

Here is the first paragraph of The Invention of Solitude:

“One day there is life. A man, for example, in the best of health, not even old, with no history of illness. Everything is as it was, as it will always be. He goes from one day to the next, minding his own business, dreaming only of the life that lies before him. And then, suddenly, it happens there is death. A man lets out a little sigh, he slumps down in his chair, and it is death. The suddenness of it leaves no room for thought, gives the mind no chance to seek out a word that might comfort it. We are left with nothing but death, the irreducible fact of our own mortality. Death after a long illness we can accept with resignation. Even accidental death we can ascribe to fate. But for a man to die of no apparent cause, for a man to die simply because he is a man, brings us so close to the invisible boundary between life and death that we no longer know which side we are on. Life becomes death, and it is as if this death has owned this life all along. Death without warning. Which is to say: life stops. And it can stop at any moment.”

For nearly forty years, Auster was my favorite living American writer. Braided into my respect and admiration for him are the coincidences and correspondences that link us to each other, some strongly, some less so, many of which are distinctive to New York. Born to a Jewish family in Newark in 1947, Auster resided in Brooklyn, the borough of my birth, for more than four decades. After his death, I was both surprised and happy to see how many friends of mine posted on Facebook that they would see him around the neighborhood, just going about his life — sans computer or smart phone. He wrote his books by hand, then used a manual typewriter. People who know me remember that I was a serious latecomer to computers and smart phones.

“I’ve been in Brooklyn for, let’s see, twenty-three and a half years. I’ve really been ensconced here for all that time,” Auster told me in a 2003 landline interview. “I like it because it’s New York and yet it’s a bit quieter, with a bit more air to breathe, more trees, a good place for me to do my work, and the heart of the city is just so close. It’s a perfect compromise.”

Don DeLillo and Paul Auster backstage prior to dual reading at 92nd St. Y in November 1990 (photo courtesy 92Y)

I met Auster several times, first at the 92nd St. Y on November 26, 1990, when he and New York City native Don DeLillo were giving a dual reading. At the end of the event, both signed autographs; I waited in the line for Auster, while my girlfriend, Ellen — who was to become my wife — waited for DeLillo. As we both approached the front, Auster called out to DeLillo, “Oh no, it’s the baseball guy.” A man was holding out a baseball to DeLillo that had been signed by many authors, including Auster. DeLillo inspected it and called out some of the other names on the red-stitched white leather orb before adding his own John Hancock.

Auster, I reminded Ellen, was a big Mets fan, as am I; Ellen loves the Yankees. Both men write about baseball in their books; DeLillo penned the extraordinary “Pafko at the Wall,” focusing on Brooklyn Dodgers left fielder Andy Pafko watching Bobby Thomson’s Shot Heard ’Round the World go over the fence to deliver the New York Giants the 1951 National League pennant. That moment haunted my parents, both Dodgers fanatics who used to walk to Ebbets Field when they were dating and head up to the bleachers. The Mets pop up in Auster’s City of Glass and his nonfiction Winter Journal, among other places.

“I’m Paul Auster, and I’m a New York Mets fan,” he announces next to author and Boston Red Sox fan Bill Corbett at the beginning of a video interview about the 1986 World Series between the two clubs. It looks as if he were at a Mets addict recovery meeting.

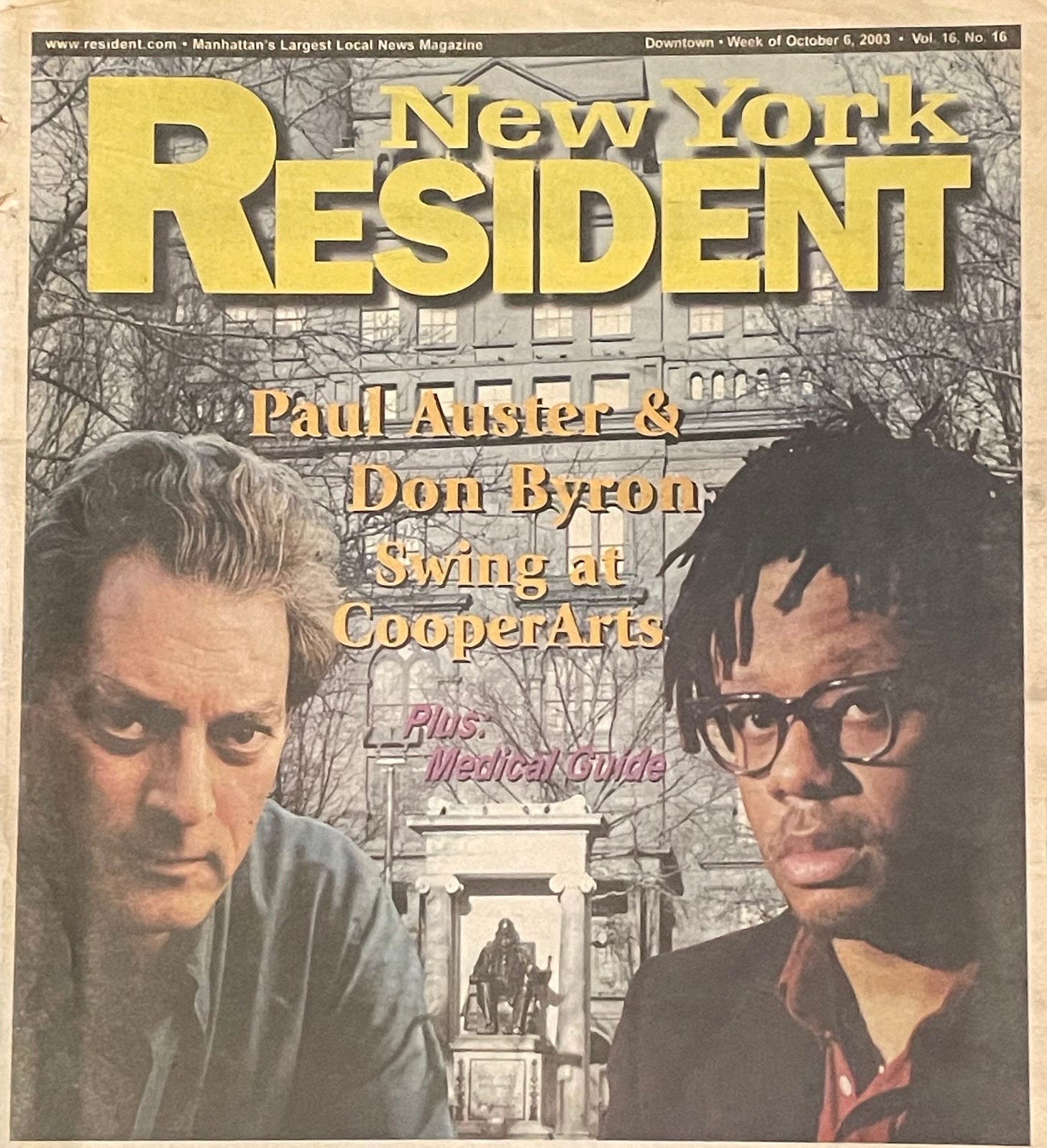

In October 2003, when I was editor in chief of New York Resident, a free city weekly, I did phone interviews with Auster and Bronx-born composer and multi-instrumentalist Don Byron about a one-night-only show they were doing at the Cooper Union with music and spoken word; the cover story was entitled: “Auster & Byron Swing at Great Hall: Bestselling Author Paul Auster and Electic Jazzman Don Byron Team Up Again for a Very Special Performance to Kick Off CooperArts’ Fifth Annual Festival.”

Looking back at it now, I am horrified to see that “Eclectic” was misspelled. But I’ll never forget the laugh Auster belted out when I presented him with a copy of the paper, with its Photoshopped cover image of him and Byron in front of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s statue of a seated Peter Cooper in Cooper Triangle. “You gotta see this,” he said to Byron as I handed Don his copy as well.

(I didn’t know it at the time, but Byron is also a fan of the squad initially incorporated as the New York Metropolitan Baseball Club; on March 29, he posted on Facebook an animated picture of Mr. Met running, with the caption: “It’s opening day for my beloved Mets. Who knew we had so many soft tissue people and a sous chef?”)

The CooperArts event was scheduled for October 9 and also featured Auster’s daughter, Sophie, who was born in Brooklyn in 1987; Sophie’s mother is author Siri Hustvedt, who married Auster in 1982. Auster was extremely proud of Sophie, who has released numerous singles and albums. “I know that parents tend to exaggerate the talents of their children, but there was no question in my mind that her rendition of [‘It Don’t Mean a Thing’] was remarkable,” he wrote in The Red Notebook: True Stories, explaining why he believed Sophie was worthy of performing the Duke Ellington classic at the Cooper Union.

As I read through my 2003 interview with the author of such other superb novels as Moon Palace, Leviathan, The Music of Chance, Oracle Night, and Sunset Park and the writer-director of the films Lulu on the Bridge and The Inner Life of Martin Frost (Auster also wrote the screenplay for Wayne Wang’s Smoke), it was hard not to think about Sophie’s older half brother, Daniel, who died of a drug overdose in April 2022 at the age of forty-four; Daniel’s mother is writer Lydia Davis, Paul’s first wife. Daniel had been arrested five days earlier in connection with the death of his ten-month-old daughter, Ruby, the previous November of acute intoxication from heroin and fentanyl.

In December 2022, Paul was diagnosed with lung cancer. His last few years were filled with one tragedy after another; as he wrote in The Invention of Solitude: “Life becomes death, and it is as if this death has owned this life all along.”

Sophie was on the cover of the September 23, 2023, issue of Mujerhoy magazine. In the accompanying article, she talks about her latest album, Milk for Ulcers, and being pregnant as her father underwent difficult treatment; she and her husband, photographer Spencer Ostrander, welcomed Miles Auster Hustvedt Ostrander into the world on January 1, 2024. “It is an album that reflects overcoming obstacles and that has given me a lot of room for maneuver to create a narrative arc and turn the grief I felt towards themes that show that I am coping with it,” she told Mujerhoy. “Writing from pain has helped me heal open wounds.”

Back in February 2016, I had also bumped into Auster. We were at the New Ohio Theatre, getting ready to watch the world premiere of Untitled Theater Company No. 61’s adaptation of City of Glass. “I have no idea what to expect,” he told me on his way in.

Untitled Theater Company No. 61 artistic director Edward Einhorn with Paul Auster at opening night of City of Glass (photo courtesy Untitled Theater Company No. 61)

In the novel, Auster wrote about the protagonist and an unnamed man who discuss baseball whenever they run into each other at a luncheonette. “They were both Mets fans, and the hopelessness of that passion had created a bond between them,” Auster explains in the book. As so many of his fans and neighbors do, I feel a bond with Auster, whose writing had such an impact on my life and career — and always makes me think of my dad. In fact, I was in Paris when I learned of my father’s sudden passing, a city where Auster worked for several years as a translator.

I will leave the last word to Auster, from The Invention of Solitude:

“In spite of the excuses I have made for myself, I understand what is happening. The closer I come to the end of what I am able to say, the more reluctant I am to say anything. I want to postpone the moment of ending, and in this way delude myself into thinking that I have only just begun, that the better part of my story still lies ahead. No matter how useless these words might seem to be, they have nevertheless stood between me and a silence that continues to terrify me. When I step into this silence, it will mean that my father has vanished forever.”

[You can follow Mark Rifkin and This Week in New York every day here.]

Thanks for the notes about the 1990 reading with DeLillo! Hadn't seen that picture before.

I saw Auster strolling down Park Slope's main drag around 1997. Thanks for this really fascinating piece--and you're very lucky to have been able to speak with him and see him face-to-face.