to tip, or not to tip?

and how much — that is the conundrum

Tip jars are now ubiquitous all around the city (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

A few weeks ago, I stopped in at Yonah Schimmel (or is it Yonah Shimmel, as it also says on the facade?) on the Lower East Side to pick up a knish, which the New York treasure has been making since 1910. I had six dollars in my pocket but the chocolate cheese knish had gone up to $6.50. There was a sign that said the credit card minimum was $10, which is the legal city limit. I decided I would buy two knishes, but the guy behind the counter said the machine had been out of service for three days.

I told him that I had only six bucks in my wallet but that I would come back and pay the remainder as soon as I was in the neighborhood again. He hesitated but decided that was fine; in the meantime, the woman next to me, who was placing a big order, suddenly decided to add a chocolate cheese knish as well after I told her how good it was.

I asked for the knish hot and ate it on the steps of Sara D. Roosevelt Park on Houston St. It was as satisfying as ever, the row of chocolate chips melting into the sweet farmer cheese and then in my mouth.

After seeing the Wangechi Mutu show at the New Museum, I found a bank, took out money, and returned to Yonah Schimmel.

“We’re closed,” the man said, then recognized me. I told him I had the rest of the money and wanted to tip him as well for being so accommodating.

He did not look happy.

I gave him $1.50 — I had been fifty cents short and decided to add a dollar tip — but he seemed insulted.

Did I do the wrong thing?

Help!!!

Knowing when and how much to tip has been a difficulty for New Yorkers forever.

In the old days, you tipped your food delivery person a few bucks when he showed up at your door, your newspaper guy at the end of the month, and your server in restaurants, who would get the most, which about fifteen years ago was either 15% or double the tax, about 16.5%. People who lived in doorman buildings also had to tip each Christmas, to doormen, porters, handymen, and the super, which could total well into the hundreds or even thousands depending on the neighborhood.

But today — and especially since the pandemic lockdown — tip jars are out in full force. Every place where you can buy any kind of food or drink has a tip jar out as well as suggested amounts, usually 18, 20, or 22 percent, if you pay by debit or credit. Whether you’re grabbing a candy bar, a cup of coffee, or an ice-cream cone, tips are requested if not expected.

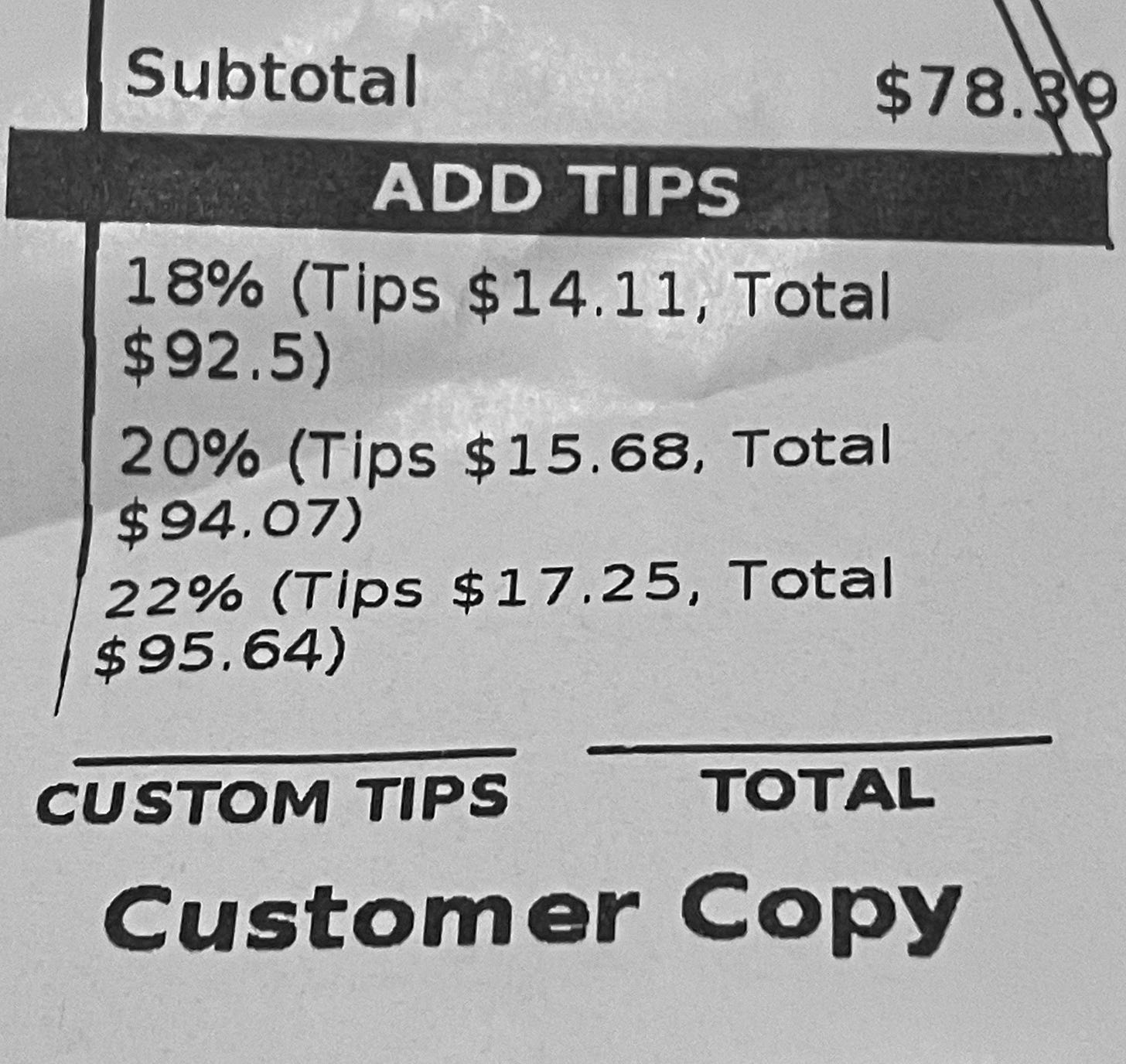

Should we tip on the tax too? (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

In the January 30 issue of New York magazine, a Grub Street article entitled “The New Rules of Tipping” pointed out what we should all be tipping at restaurants (20–25%), for coffee (20%), for food delivery (the greater of $5 or 20%), for takeout (at least 10%), at a bar ($1 per drink or 20%), at deli counters (10%), to cabdrivers (20%), and to hairstylists, nail technicians, house cleaners, and waxers (20%).

In the March Grub Street article “I Manage a Restaurant. Tips Have Never Been More Volatile.,” Emma Steiger of Oxalis and Place des Fêtes wrote, “Like it or not, tipping is a non-optional aspect of dining out in America, and the expectation is that diners will add a tip of around 20 percent to their bill. You can argue with the system, or point to its flaws, but by now, we all know the rules, and this money is our staff’s living wage. Anyone who is eating out in 2023 should recognize the work that goes into great hospitality. Instead, at least once a night and often more, I am put in a position where I have to speak to a guest who has decided to undertip. This wasn’t happening three years ago.”

But even when you do tip, particularly on a card, you’re liable to feel cheap because your choices have gone up. Several online guides suggest that you should tip 15–20% for a cab ride, but the predetermined options when you pay with a card are 20, 25, or 30%. At a restaurant last week, the bill offered me options of 18, 20, or 22%, doing the math for me, but I couldn’t help but notice that we were tipping on the tax as well, not the base price. At Citi Field for an NYCFC soccer match, I bought two beers, Cracker Jack, and fries and could tip, if I remember correctly, 5, 7, or 9%, which made me wonder about the power of their union.

You are often, but not always, given the option of a custom tip, which I will sometimes use when I’m getting a small item, say, a four-dollar cookie. I also like to travel around with singles in my wallet for just such an occasion, but I have to admit that I wait to make sure the worker has seen me put a tip in the jar, especially if it’s a local place I frequent. If a tip falls into a jar and nobody sees it. . . .

In the 1996 Seinfeld episode “The Calzone,” George (Jason Alexander) agonizes when picking up his food in a pizza place. “I go to drop a buck in the tip jar, and just as I’m about to drop it in, [the calzone guy] looks the other way,” George tells Jerry. “So then, as I’m leaving, he gives me a look like, ‘Thanks for nothin’.’” Jerry says, “You got no credit,” to which George replies, “Exactly. It’s like I’m throwing a buck away. If they don’t notice it, what’s the point?”

In an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, Jason Alexander and Larry David split the check at lunch, but Larry gets angry when Jason refuses to tell him how much he is tipping; Larry wants them both to leave the same amount, but Jason refuses to take part in any kind of “tip coordination.” We later learn that he left much more than Larry did both to embarrass the star and to get better service in the future.

The tipping conundrum is now reaching the next level. In the May 9 Wall Street Journal article “Tipping at Self-Checkout Has Customers Crying ‘Emotional Blackmail,’” Rachel Wolfe writes, “Prompts to leave 20% at self-checkout machines at airports, stadiums, cookie shops, and cafes across the country are rankling consumers already inundated by the proliferation of tip screens. Business owners say the automated cues can significantly increase gratuities and boost staff pay. But the unmanned prompts are leading more customers to question what, exactly, the tips are for.”

What exactly are we tipping for? It’s a legitimate question. Tipping after a meal or a ride makes sense; you can actually base the amount on the service you received, on how good the food was or how smooth the ride was. Alternately, you can tip less if the food was terrible, the server rude, or the driver loud and obnoxious and didn’t know where he was going. Or you can tip for bad service because you’re softhearted: In an episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Mary sneaks a tip under a plate after Lou (Ed Asner) has opted to leave nothing because of poor service.

But when you’re not served at a table in a restaurant and instead leave the tip when you pay for your order up front at the counter, what’s to be done if your food comes late and is terrible? You can’t demand part of your tip back, but you can cross that restaurant off your list. But what if it was just an off night or they had a bad employee they have since gotten rid of? Why are we tipping in advance? Is it the consumer’s responsibility to make up for a worker’s low salary? If someone comes to fix my refrigerator, I tip them when the job is completed, not before it starts, and I base it at least in part on whether they did a good job.

Questions about tipping go back centuries. In the November 2015 NPR article “When Tipping Was Considered Deeply Un-American,” Nina Martyris explains, “When tipping began to spread in post–Civil War America, it was tarred as ‘a cancer in the breast of democracy,’ ‘flunkeyism,’ and ‘a gross and offensive caricature of mercy.’ But the most common insult hurled at it was ‘offensively un-American.’” Since then, it’s become peculiarly American. Tipping is very different in Europe, where food-service workers earn full salaries and are not paid below minimum wage, as waiters are here, many of whom depend on tips to pay their rent. Before the pandemic, restaurateur Danny Meyer implemented tip-free restaurants, raising overall prices about fifteen percent to cover what would have been gratuities and paying that money directly to the staff, but the experiment was a failure.

As the coronavirus crisis took hold, delivery people, who became known as gig workers, were a lifeline for so many Americans, bringing just about whatever we wanted and needed to our doorsteps, saving us from having to venture into the Covid-filled world. In a May op-ed in the Daily News, Ligia Guallpa of the Worker’s Justice Project and Vincent Alvarez of the New York City Central Labor Council, AFL-CIO, wrote, “Delivery workers were essential during the pandemic. They worked countless hours and braved rain, snow, and extreme flooding while being the targets of street crimes, evading dangerous traffic, and spending hundreds on the equipment they rely on to do their jobs. Today, New York delivery workers take home $11 an hour after tips. Some spend close to $17,000 a year on operating expenses alone. Many delivery workers are lucky to make it home safe — if at all.”

How automatic should tipping be, how much and on what occasions? In the long run, the difference between 18, 20, and 22% could be just a few dollars, which the tippee could most likely use much more than the tipper. The other day, I felt that tipping 20% to an employee for a prepackaged cookie was too much, so I left a dollar instead. On my way out, I realized that the dollar was more than 20%, but I eventually got over it.

As noted above and below, tips are often treated as jokes in film and television. In Caddyshack, Carl Spackler (Bill Murray) shares the tale of when he caddied for the Dalai Lama on a Tibetan golf course: “So we finish eighteen, and he’s gonna stiff me. And I say, ‘Lama, hey, how about a little something, you know, for the effort, you know.’ And he says, ‘Oh, uh, there won’t be any money, but when you die, on your deathbed, you will receive total consciousness.’ So I got that going for me, which is nice.”

In a recent Substack post, I detailed a long-ago problem about not receiving my newspapers at the door of my apartment every morning, making me consider, “to tip, or not to tip.” I leave it to Mel Brooks to have the final word on the subject (and indeed, stick around for that final word about Dennis the hotel bellboy, played by future director Barry Levinson):

Get the substack! Get the substack! Where do I tip?

I will not participate in this offloading of employee salary onto consumers. I will tip generally 20 percent at restaurants, occasionally the leftover change if I order coffee at a counter (I usually pay cash for that). Food delivery is a dollar amount, usually like $7, not a percentage, NEVER at self-checkout. Any counter service, at most, for an order that requires more than grabbing and handing to me, I throw in a dollar or so in the jar.

And assuming I had had $6.50 for a knish, NO, I wouldn't tip for that. Period.

It's inherently privileged and elitist as often folks retort, "If you can't afford an additional 25% on top of the cost of anything you purchase, then make it yourself." This tipping for everything is a very new thing. No one tipped for everything before say, 10-15 years ago. This "sharing economy" is exploitative--tipping in general is a remnant from slavery and Jim Crow days.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/05/opinion/minimum-wage-racism.html#:~:text=After%20the%20Civil%20War%2C%20white,to%20show%20favor%20to%20servants.