rubén blades’s “maestra vida”: celebrating a visionary artist at lincoln center

Rubén Blades performs Maestra Vida with the New York Philharmonic at Lincoln Center in March (photo by Lawrence Sumulong @layer_nyc)

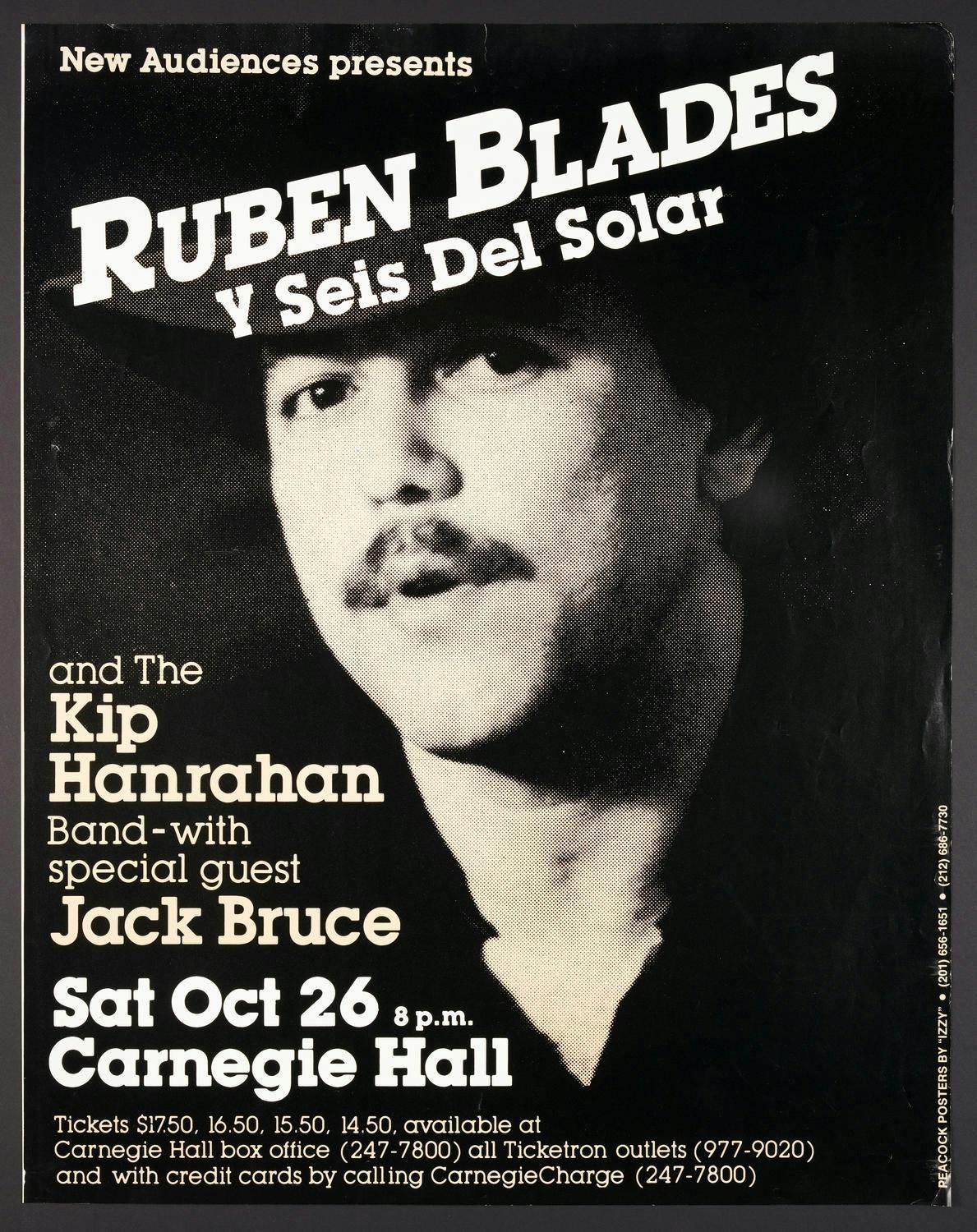

On October 26, 1985, I saw Rubén Blades make his Carnegie Hall debut, with his band Seis del Solar. The Panamanian singer-songwriter was in the midst of becoming an international salsa superstar. He was touring behind his breakthrough records, 1984’s Buscando América and 1985’s Escenas — the former featuring such powerful tunes as “Decisiones” and “Desapariciónes,” the latter boasting such gems as the jazzy “La Canción del Final del Mundo,” the showstopper “Muévete,” and “Silencios,” a gorgeous duet with Linda Ronstadt — and would soon play the lead role in Leon Ichaso’s Crossover Dreams and appear in Robert Redford’s politically tinged The Milagro Beanfield War with Sônia Braga, Melanie Griffith, John Heard, Daniel Stern, and Christopher Walken.

Winner of twelve Grammys and a dozen Latin Grammys, Blades, a two-time Emmy nominee who has law degrees from the University of Panama and Harvard, also attempted to unionize New York Latin musicians in 1980, ran for president of his native country in 1994 (receiving seventeen percent of the vote), and was named Panama’s tourism minister in 2004.

On March 31, I was at Lincoln Center’s Wu Tsai Theater in David Geffen Hall for the US premiere of his 1980 song cycle, Maestra Vida. Blades, now seventy-six, performed the show with a five-piece salsa band, three vocalists, and approximately eighty members of the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Venezuela-born Diego Matheuz in his NYP debut, joined by special guests Ella Bric on trumpet, the colorfully dressed Xito Lovell on trombone, and Luba Mason, Blades’s wife, on vocals. In his trademark black outfit with black hat, Blades and narrator Dr. Carlos Chirinos, an NYU assistant professor and Lincoln Center Latin music curator, told the epic fifty-year tale of a family in an unnamed, tight-knit Latin American community.

“I wanted to create a musical document that would reflect the reality of the Latin American working-class neighborhood, just as I knew it growing up in Panama,” Blades writes in a program note. “From the beginning of my career as a composer, I sought to base my songs on themes that would not only entertain and amuse the listener but also serve to describe, document, and expose social, political, and human realities. One of my goals was to educate by sharing experiences that I considered common to city dwellers, presenting perspectives that could provoke empathy, discussion, and, why not, controversy.”

The narrative follows the touching relationship between Manuela Peré, the Venus of the barrio, and Carmelo DaSilva, a tailor known as the Prince of the Hustlers. They meet such characters as Vavá Quiñones, Foncho Linares, and Franklyn “Crime Face” González in “the alley of the bored people,” have a son named Ramiro, and seek happiness as the family encounters hunger, misery, loss, and corruption along with love, hope, joy, and faith.

Among the songs, which are sung in Spanish with English surtitles, are “Yo Soy una Mujer” (“I Am a Woman”), “Déjenme Reír (Para no llorar)” (“Let Me Laugh [to Not Cry”]), and “El Velorio” (“The Wake”). Memorable lines pop up again and again: “Master life, friend / It gives you and takes away and takes away and gives you”; “United / I swear until I die / I won’t stop loving you”; and “When he grows up, what will he be, what will he be, what will he be . . . / Will he perhaps be a baseball player like Aparicio, or Clemente, idol of his people / And glory for baseball?”

Watching the fabulous show, it’s hard not to think about how it feels so much like New York, not only because of the sense of local community it celebrates but because Lincoln Center itself was built on San Juan Hill, where seven thousand Black and Latino families and eight hundred businesses thrived in the 1950s until Robert Moses razed it as part of the Lincoln Square Development Plan, an urban renewal project that Lincoln Center details in an online site where they honor what came before. (San Juan Hill was also the setting of West Side Story.)

In 2025, Blades’s Panamanian roots also bring up Donald Trump’s desire for the United States to take over the Panama Canal. In 2007, Blades told the Tico Times, “Panama’s success in administering the canal destroys the argument that a third-world country cannot successfully manage its own resources.”

It’s a shame that the glorious Maestra Vida had only two performances with the philharmonic; it is worthy of a much longer run and needs to be seen by many more people, especially in America at this moment in time. Maybe the Kennedy Center will pick it up.

“Lincoln Center Visionary Artist: Rubén Blades” began last fall and continues on May 14 at 6:00 with a screening of Crossover Dreams at the Walter Reade Theater, followed by a Q&A with the film’s Cuban-born producer and cowriter, Manuel Arce. And through April 15, Lincoln Center is hosting the exhibition “From Panama to New York: The Musical Journey of Rubén Blades” at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

[You can follow Mark Rifkin and This Week in New York every day here.]