Maurizio Cattelan’s America let Guggenheim visitors go in style (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

In this ever-evolving world where privacy is becoming a lost art, there are still some moments that need not be made public. For me, going to the bathroom is one of them.

When I was a kid, my parents were very open about their relationship, spending many a Sunday morning in the bathroom together, the door wide open for me, my brother, and my sister to witness their overabundant affection.

I prefer the bathroom door be closed – and locked tight – when I’m on the bowl. I well remember when the lock on that bathroom door at my mother’s house didn’t work anymore, so when I was there visiting her or for a family function, I was petrified that someone might walk in on me while I was doing my business, even though it would most likely just be a very close relative. Still, I tried to block the door with towels or the hamper, praying that no one would prance right in on me.

The bathroom door in my apartment doesn’t shut all the way, as the room was built on a curve. It doesn’t bother me when one of our cats nudges open the door and jumps onto me, although I don’t feel the same way about my wife, even after thirty years of marriage. When we have guests over, I am somewhat embarrassed to have to explain to them that the john door doesn’t quote snap closed, but no one seems to mind.

Which brings me to a traumatizing event that happened to me back in August 2011. I was at the funky Gershwin Hotel (now the Evelyn) near Madison Square Park, where the Amoralists were presenting HotelMotel, a pair of full-length plays staged in a converted room at the back of the lobby. Not quite knowing what to expect but realizing the audience, limited to twenty people per show, was going to be in close, intimate quarters with the performers, I decided to make a preemptive visit to the head in Birch Coffee, which was connected to the Gershwin.

The bathroom was tiny, with barely space for my knees to avoid the sink as I was sitting down. Although I had locked the door, the handle felt shaky; I didn’t trust it, worrying about a weak bolt. After a few minutes, I prepared to leave when I heard someone grab the doorknob. Immediately filled with fear, I called out, “Just a minute” as I painfully watched the knob slowly twist.

And then, with me still on the terlet, my pants around my ankles, the door flung open and a young man peered in at me: My worst fears suddenly realized.

The dude just stood there looking down at me; behind him I could see a woman typing away on her laptop, as well as people walking up and down Twenty-Seventh St., passing by the large plate-glass front window. I thought of the old Jonny Cat ad in which a kitty, seeing he is being watched in his litter box, says to the viewer, “Do you mind?” Except I was not so self-composed

After a few dramatic seconds, the guy was still staring at me, just standing there.

“Shut the fucking door!” I screamed at him.

The door started to close, then swung open once more as he looked at me again and said, “Take it easy, man. Chill.”

Another person passed by on Twenty-Seventh St.

“What’s wrong with you!” I shouted. “Shut the motherfucking door! Now!”

He closed the door.

I was petrified, frozen for a long moment, except for my heart, head, and stomach, which were shaking uncontrollably inside me. For years, I have had nightmares in which I desperately have to powder my nose but only find stalls with no doors and with crappers that are beyond filthy, overflowing with crud and me without shoes, needing relief terribly but adamantly refusing to go under those circumstances.

According to dreammoods.com, that means I have general privacy issues as well as very specific difficulties revealing and releasing my emotions, that I need to “relieve” myself of inner burdens in order to cleanse myself both psychologically and emotionally in a ritual of purification and self-renewal.

And I am not alone.

Web4health.info notes that “up to six percent of the population has a severe fear of using public toilets,” suffering various anxieties related to cleanliness and contamination, being locked in a confined space, and having a bashful bladder or sphincter, among other fears. Meanwhile, the national registered charity Anxiety UK dedicated an entire project to toilet phobia, examining agoraphobia, parcopresis, paruresis, panic disorder, OCD, and other public-bathroom-related psychological problems.

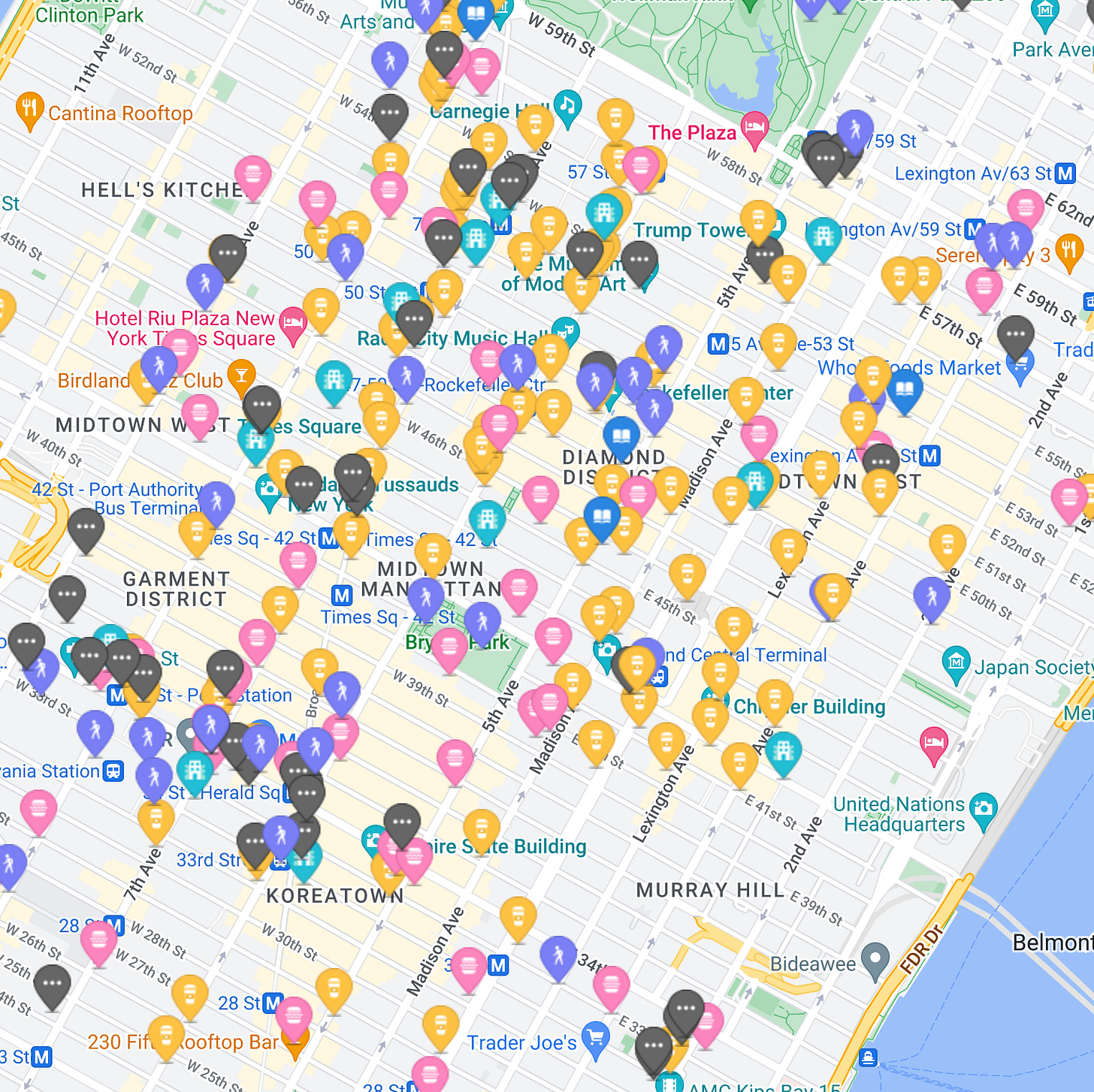

The website nyrestroom.com helps where to find public bathrooms (image courtesy nyrestroom.com)

Finding a public bathroom in New York City has long been an issue. There are plenty of online articles and apps pointing out where to find a loo, but that doesn’t mean they are going to be open and well maintained, with locks on the door and no ridiculously long lines, like at Bryant Park.

I’ve never been a fan of the self-washing automatic public toilets the city occasionally tests, which cost a quarter and open up after fifteen minutes, whether you’re finished or not, exposing the occupant to whoever is outside.

One friend of ours turned us on to the spectacular gold, mirrored Prada bathroom on Fifth Ave., so we pretended we were shopping there (do you “shop” at Prada?) just so we could feel okay using the can, and it was everything she promised.

In 2016, the Guggenheim installed Maurizio Cattelan’s America in its fifth-floor single-occupancy rest room, a fully functional eighteen-carat solid-gold throne that the Italian artist called the “Guggen-head . . . one-percent art for the ninety-nine percent.” That one was worth waiting on line for.

Back at the Birch, I gathered myself together, pulled up my pants, washed my hands, took a deep breath, and walked out of the tiny bathroom, visibly shaken and uneasy. The guy who had breached my privacy — not once but twice — was sitting there and got up to use the bathroom without apologizing.

“Dude, what the fuck?” I said.

“What’s wrong with you?” he answered. “Chill out already. The door wasn’t locked.”

“Chill out? First of all, the door was locked. But why did you open it a second time after you already knew I was in there?”

“I was freaked out,” he said, as if his experience were more traumatic than mine.

“You were freaked out?! Imagine how I felt,” I said, but he had turned around and was already walking into the bathroom. I looked around the coffee shop, seeing that nobody else seemed to be imagining how I felt either; they were ignoring the scene or looking at me with disdain for having disrupted their peace.

I approached the counter, where I asked two of the employees if they had seen what had happened; they just turned away, as if I wasn’t even there.

Upset, angry, and filled with rage, I went back into the lobby, where we were soon escorted into the hotel room theater, where we watched Derek Ahonen’s very funny relationship comedy Pink Knees on Pale Skin, in which a therapist claims she can cure two couples’ sexual problems by having them swap partners and participate in an orgy.

During the twenty-minute intermission between shows, I went for a walk and called my wife from a pay phone, but I was still deeply troubled by what had happened at the Birch. My entire life I had avoided this awful event from occurring and boom, it finally had struck, and it was all I had feared and more.

Crossing the street, I had to get out of the way of a skateboarder going through a red light.

“What the fuck?!” I called out to him. He got off his skateboard and started to come at me, looking for a fight, claiming he wasn’t close to hitting me. After we nearly came to blows, I went back into the Gershwin, shaking yet again, knowing I was going to have to reach deep inside myself to examine my reactions to the events that were overwhelming me.

For the second play, Adam Rapp’s complex, surreal Animals and Plants, about a pair of small-time hoodlums snowed in at a North Carolina motel, the audience gets to choose where they want to sit, with most chairs together in two rows on one side of the room but a handful placed within the claustrophobic set. For some reason, I opted for the chair that was set against the far wall, next to a night table, right in the middle of much of the action. I knew that I had trapped myself; once the play started, it would be impossible for me to get up to go to the bathroom or do anything else. In fact, every move I made would be seen by the rest of the audience as well as the actors.

But I decided that I would not be afraid. I would sit right there and take whatever comes.

The Amoralists’ Animals and Plants took place in a room at the Gershwin Hotel (photo by Russ Rowland)

A few minutes into the show, the tougher of the two thieves, Burris (Matthew Pileci), walked right up to me and reached out his hand. I didn’t think I was supposed to take it, but before I could figure out what was going on, he grabbed a knob by my right shoulder and opened a bathroom door. He pulled down his briefs and began to take a dump, leaving the door wide open, with me right there, peering in. Because of the placement of the toilet, I was among the very few audience members who could actually see exactly what he was doing. And he seemed to really be doing it, judging by the sound of things. I nodded to the others, basically telling them, “Yup.”

At that moment, I could feel my fear and anger over what had happened at the Birch flush out of me. A few hours before, I had been trying to go to the bathroom when one of my worst fears turned into a reality and a stranger walked in on me. And now here I was, sitting in the middle of a stage set in a hotel, with a man taking going number two right next to me, without a care in the world that people were looking in at him, some straining their bodies in order to get a peek.

Burris took care of business, then came back into the room as if it had been no big deal. And indeed, it had been no big deal, just part of the show.

I sat more comfortably through the remainder of the bizarre but entertaining play, then walked home, amazed by what I had experienced. An epiphany? A “Eureka!” moment? A sign from the heavens? A mere coincidence?

Whatever it was, it filled me with a warming calm that made it feel as if I were floating down the street. Facing your fears is supposed to be a life-changing experience. That day, I felt changed.

But the next day, if I had to use a public bathroom, I was going to make damn sure the door was locked, and locked good and tight.

I am still traumatized by an incident in first grade when I apparently didn't fully shut the bathroom door, and my entire class heard me in there. But that doesn't compare with the horror of being in an airplane restroom during major turbulence. I'm not afraid of public bathrooms on land anymore, just those in the air.

What the HELL?!