Faith Ringgold stands in front of her quilt Tar Beach (photo by AP/Kathy Willens)

Did you hear?

Faith Ringgold died on April 12 at the age of ninety-three.

I found out not on the news — either online or in the paper — but from a Facebook friend’s post several days later. And that’s a shame.

Born in Harlem on October 8, 1930, Ringgold was a trailblazing painter, quilter, mixed-media sculptor, performance artist, author, teacher, historian, mother, and activist — but primarily a master storyteller.

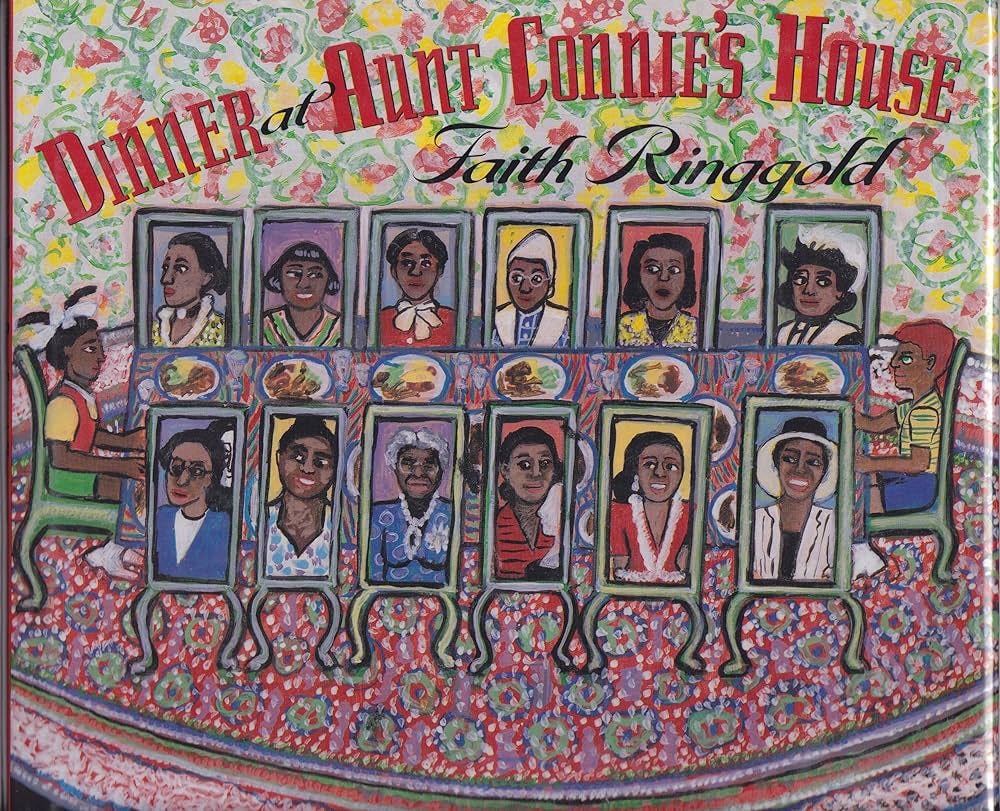

I have always felt a special connection to Ringgold. In 1992, I had the sincere privilege of working on her second picture book for children, Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House, the follow-up to her award-winning debut, Tar Beach. Based on her 1986 painted story quilt The Dinner Quilt, the book features twelve prominent Black women: Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer, Mary McLeod Bethune, Augusta Savage, Dorothy Dandridge, Zora Neale Hurston, Maria W. Stewart, Bessie Smith, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Marian Anderson, and Madame C. J. Walker. Each woman shares her personal journey with a young girl named Melody, through portraits made by her aunt Connie.

I was aware of most of the women in the book, primarily because at my first job out of college, at a small company that published nonfiction books for children, we produced a series called “Black Americans of Achievement.” But they were not all household names, especially in those pre-Google days.

In fact, Truth is one of only two females of color — the other is Sacagawea — who makes the cut in the thirty-nine mythical and real women who have a place setting in Judy Chicago’s 1974–79 installation The Dinner Party, a feminist milestone that is on long-term view at the Brooklyn Museum; Bethune, Savage, Hurston, Stewart, Smith, Tubman, and Anderson are listed among the 998 women in the piece’s Heritage Floor. There’s no mention of Hamer, Dandridge, or Walker.

Truth’s Dinner Party plate is one of only a few that does not contain a vulvar image. In a 1979 Ms. magazine article, Alice Walker wrote about the work, “Perhaps white women feminists, no less than white women generally, cannot imagine black women have vaginas. Or if they can, where imagination leads them is too far to go.”

In the afterword of Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House, Ringgold explains, while the book “shares many elements with The Dinner Quilt, the story changed as it was transformed from a story for adult audiences to a story for children. I intended the original story for adults to recall their childhood memories of good times at festive dinners, with relatives and close friends, sharing family stories and delicious food. . . . Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House is an expression of my belief that art can be more than a picture on a wall — it can envision our history and illustrate proud events in people’s lives. And what’s more, it can be magical!” That’s precisely what so much of Ringgold’s art accomplished.

Faith Ringgold’s 1986 The Dinner Quilt led to the book Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House (©️ Faith Ringgold)

When MoMA reopened in October 2019 after a major revamping and expansion, crafting new dialogues between artworks across time and genre, Ringgold’s 1967 painting American People Series #20: Die, a Guernica-inspired canvas about race, class, and violence, was in the same room with thirteen works by Pablo Picasso (from 1905 to 1912) and Louise Bourgeois’s 1947–53 Quarantania, I sculpture.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #20: Die, oil on canvas, two panels, 1967 (the Museum of Modern Art, New York. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022. Digital Image © the Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY)

On MoMA’s audioguide, Ringgold recalls, “There was a lot of spontaneous rioting and fighting in the street and undocumented killings of African American people, and great racism. Everybody knew. Everybody talked about it, but I would never see anything about it on television — nothing. How could I, as an African American woman artist, document what was happening all around me? . . . I had the courage to go ahead and speak out. I want you to be upset. You’re not supposed to see people rioting and killing each other or even know that they’re hating each other without being upset. This was going on then; it’s happening again now. And every time I see one of those big riots in the street here today, I think back to Die.”

In 2022, the New Museum hosted the revelatory “Faith Ringgold: American People,” a multifloor retrospective that included a dozen art-history-influenced narrative quilts, such as Dancing at the Louvre: The French Collection Part I, #1; Picasso’s Studio: The French Collection Part I, #7; The Sunflowers Quilting Bee at Arles: The French Collection Part I, #4; and Matisse’s Model: The French Collection Part I, #5.

Faith Ringgold’s The Picnic at Giverny is a story quilt from her “French Collection” series (© Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022)

In The Picnic at Giverny: The French Collection Part I, #3, the series’ sixteen-year-old protagonist, Willia Marie Simone, declares in a letter to her aunt Melissa, “Should I paint some of the great and tragic issues of our world? A black man toting a heavy load that has pinned him to the ground? Or a black woman nursing the world’s population of children? Or the two of them together as slaves, building a beautiful world for others to live free? Non! I want to paint something that will inspire — liberate. I want to do some of this WOMEN ART. Magnifique! . . . I paint like a woman. I always paint wearing a white dress. Now I have a subject that speaks out for women. I can no more hide the fact that I am a woman than that I am a Negro. It is a waste of time to entertain such subterfuge any longer.”

(Last fall, the New Museum held the multifloor retrospective “Judy Chicago: Herstory,” which was highlighted by the controversial “The City of Ladies,” an exhibit consisting of works and archival materials from more than eighty women and genderqueer artists, writers, and thinkers, with Truth and Hurston represented.)

Faith Ringgold, Street Story Quilt, cotton canvas, acrylic paint, ink marker, dyed and printed cotton, and sequins, sewn to a cotton flannel backing, 1985 (© 1985 Faith Ringgold)

The other night, my wife and I were out having dinner with dear friends of ours. Shortly afterward, I found out that one of the couples had a fascinating connection to Ringgold.

Arts writer, photographer, educator, and curator Barbara Pollack, cofounder of Art at a Time Like This, disclosed to me, “I worked for Faith in the mid-1980s, stitching her quilts on a sewing machine while she painted, and talked, and talked, often delivering speeches about how to survive the art world that were invaluable life lessons for this budding artist.”

Pollack worked on the Street Story Quilt trilogy, which was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1990 and contains three versions of the facade of a Harlem building across three decades: “The Accident,” “The Fire,” and “The Homecoming.”

“The most important thing Faith ever told me,” Pollack said, “was, ‘Begin every September as if you have a show in June. That way, by the time “they show up,” you’ll be ready.’ I still work that way.”

Pollack’s husband, civil rights attorney Joel Berger, added, “In the mid-1980s, there was an art exhibit in the lobby of the old Manhattan federal courthouse (now named the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse), and it included one of Faith’s quilts. It was typically political and had lots of symbolism about racial issues. A senior clerk for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (on which Marshall had served before being appointed to SCOTUS) who had administrative power over the building found the quilt offensive and had it taken down. I was with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund at the time, and Barbara and I helped organize a campaign to have the quilt put back up. We got the Federal Bar Council and other lawyer and arts organizations to chime in. The chief judge of the Second Circuit and possibly other judges took note and overruled the clerk; the quilt quickly reappeared. We called it ‘the Case of the Radical Quilt.’”

In Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House, Melody’s cousin Lonnie asks Parks, “How can you speak? Paintings don’t talk like people.”

Parks replies, “Your aunt Connie created us to tell you the history of our struggle. Would you like to hear more?”

It’s a shame we won’t be able to hear more from Ringgold, but her work will continue to speak volumes to future generations.

[You can follow Mark Rifkin and This Week in New York every day here.]

I'm so glad you wrote about Faith Ringgold, what an amazing person. I love those quilts, especially The Picnic at Giverny. Such a loss for all of us.