The one and only Austin Pendleton and me at Theater for the New City after a performance of Orson’s Shadow (photo by twi-ny/ees)

I’ve been obsessed with Austin Pendleton for most of my life.

And that obsession has only grown since I interviewed him a few weeks back about the twenty-fifth-anniversary revival of one of the three plays he’s written, Orson’s Shadow, which concluded a short run at Theater for the New City on March 31. The show is about another one of my obsessions, Orson Welles, as he directs Laurence Olivier and Joan Plowright in the first English-language production of Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, during Sir Larry’s breakup with Vivien Leigh. You can read the first part of the interview here.

When I was a kid, my parents, who loved going to the theater, had a handful of cast albums on vinyl or 8-track; I listened over and over to Hair, Man of La Mancha, West Side Story, and, primarily, Fiddler on the Roof. For some reason, I was drawn to Motel Kamzoil, the tailor in Fiddler who falls in love with Tzeitel, the oldest daughter of Tevye the milkman and his wife, Golde, in the eastern European village of Anatevka.

Leonard Frey played Motel in the film, but Pendleton originated the character and was on the record, singing “Miracles of Miracles,” a song I’ve been known to break out into at the spur of a moment.

“When David slew Goliath — yes! — that was a miracle. / When G-d gave us manna in the wilderness, that was a miracle too. / But of all G-d’s miracles large and small, / the most miraculous one of all / is the one I thought could never be: G-d has given you to me.”

Even if you don’t recognize the name, you’ve seen Austin Pendleton. He has more than two hundred theater, film, and television credits; among his most famous roles are public defender John Gibbons in My Cousin Vinny, Max in The Muppet Movie, and the voice of Gurgle in Finding Nemo and Finding Dory. He played recurring characters on Homicide and Oz and had key parts in such films as Catch-22, Short Circuit, and What’s Up, Doc?

He’s been nominated for a Tony for Best Direction of a Play for 1981’s The Little Foxes, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Maureen Stapleton, won an Obie for directing 2011’s Three Sisters with Maggie Gyllenhaal, Peter Sarsgaard, Jessica Hecht, and Juliet Rylance, and was named a Renaissance Man of the American Theatre in 2007 by the Drama Desk.

I’ve met Pendleton several times at the theater over the years, just to say hello and gush to him for a minute or two. I even chose to sit next to him when he was up for a 2015 Drama Desk Award for his direction of Stephen Adly Guirgis’s Between Riverside and Crazy. (“That was a heavenly show,” he would tell me later.)

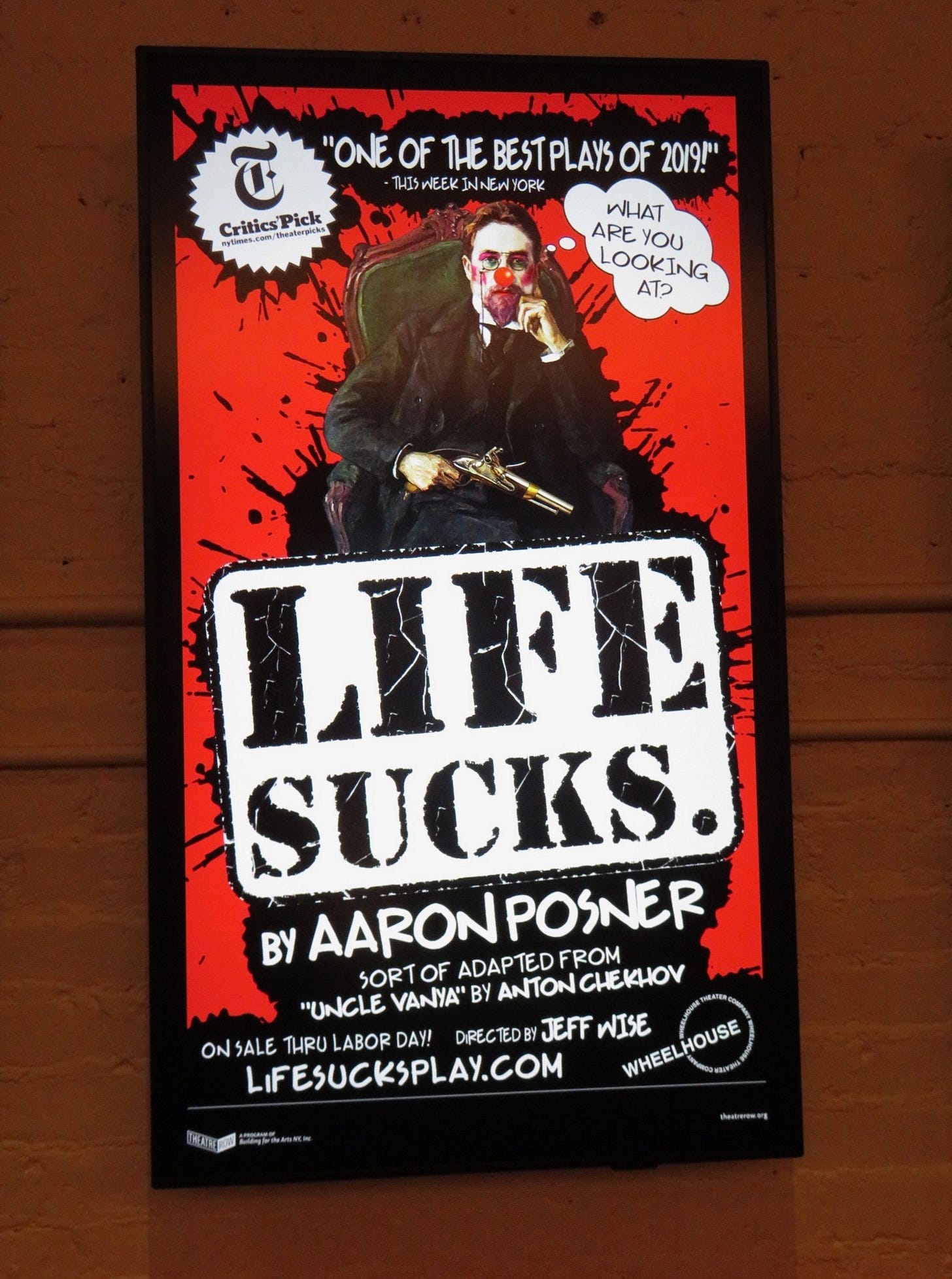

A few years ago, I bumped into him waiting for the Third Ave. bus at Fourteenth St. We had a wonderful conversation, beginning with my explaining how much I had loved Life Sucks., Aaron Posner’s adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya at the Wild Project in which Pendleton portrayed the elderly professor. In fact, I told him that the ad for the show on that very bus kiosk included my declaration that it was one of the best shows of the year. We continued our talk on the bus as we headed uptown, chatting about his long and varied career.

I reminded him of that meeting at the start of the interview, which was supposed to last fifteen minutes to a half hour but went on for an hour and a half; although I wanted to keep talking to him, I had to leave to go to a hockey game at the Garden.

The interview was everything I wanted it to be and more. Pendleton was generous with his time and insight and was relaxed and friendly. For most of the talk I could see only the top half of his face, his white hair unkempt, and at one point he shaved while we spoke, not because he was in a rush to get anywhere but just because.

Midway through, anxiety struck: Pendleton had some trouble with Zoom and needed to leave and reenter. Doing so took several minutes, and I fretted he wouldn’t be able to return. To my, and his, delight, he was able to sign back in, proceeding to regale me with remarkably intimate stories about working on Fiddler with director and choreographer Jerome Robbins and producer Hal Prince, then turning his attention to his long relationship with the plays of Tennessee Williams.

I didn’t have to say much; I just let Austin run with it.

Austin Pendleton and Joanna Merlin played husband and wife in Fiddler on the Roof

austin pendleton: You know about all the travails of Fiddler on the Roof when it was in its out-of-town tryouts, right?

Well, it played for five weeks in Detroit, and then a little under three weeks in Washington, and then just a handful of previews in New York. In Detroit, it got, well, particularly the Variety review.

If you want to entertain yourself, pull up the Variety review in August 1964 from Detroit of Fiddler on the Roof. It’s one of the worst out-of-town reviews of a musical they ever had. [ed. note: An extensive internet search came up empty.]

twi-ny: Was it the same cast?

ap: Yeah, we it was the pre-Broadway tryout. We were on the way to Broadway.

twi-ny: Were there significant changes made because of that?

ap: Jerry [Robbins] did this amazing thing. And I think what I’m going to quote him as saying is going to be the title of my memoir. So the Variety review came out. And it was a Wednesday, but we didn’t have a Wednesday matinee that day and we were rehearsing all day. And people were aware of the review. And people were crying in the dressing rooms and all that. And then we did the evening show in Detroit. And there was a bar across the street that we always went to. I hope that bar is still open, if I’m ever in a show in Detroit again, because a whole lot of wonderful, heavy times went down there in that bar.

But anyway, in the back of the bar, it was brightly lit. And in the front part of the bar, it was not brightly lit. So I walk in. For some reason, I was a bit late getting across the street to the bar. I don’t know why.

I was heading toward where all the actors were in the back and there was Jerry at the front, which was not well lit; he was just looking very relaxed. Because I had worked with him once before in Oh Dad, [Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feelin’ So Sad] I felt emboldened to say, Jerry, what are you going to do?

And he looked up calmly from his martini and said, “Ten things a day.” That’s going to be the title of my memoir. And he held to that. He did detail work. Over the years, friends of mine have been in big shows with out-of-town tryouts, like up in Boston. My sister lives up in the Boston area. When I’m up there, I’ll go see my friends in out-of-town tryouts and go to some of the opening nights. After, there’s a party and the producers will be looking real anxious.

Those shows won’t be in anything like the kind of trouble that Fiddler was in. I’ll be talking to the producers and I will quote them what Jerry said: “Ten things a day.” But then they would usually freak out, and fire people, and cut out whole things and add things.

Of course, the show comes to New York, and what was a promising show is now a disaster.

But Jerry did ten things a day. It was detail work for the rest of the Detroit run, which still had quite a few weeks to go. Like rehearsing scenes: If in a speech you crossed the room a sentence earlier to do some task, that will show that you’re not completely accepting what the characters is saying, stuff like that. And to [book writer] Joe Stein, if you cut one sentence out of this little speech or if you add one sentence. . . .

Then we opened in Washington and we got raves, probably the best reviews the show ever got.

Everybody turned on each other savagely once the siege mentality had lifted and all the tensions that had been building up exploded. And that was the only time that Jerry and I ever had a fight.

I announced to his assistant that Jerry was not to speak to me for a week. And in the middle of that week, we had to rehearse for the new song I had, called “Miracles.” I got that song because of a whole series of events. I had a song called “Now I Have Everything” in Detroit. Bert Convy, who was playing Perchik, the revolutionary, was a dressing roommate and remained a good friend of mine for years after the show; he had a song beginning the second act that must surely have been the worst song that [Sheldon] Harnick and [Jerry] Bock ever wrote. Bert Convy had a powerful voice; he was a great actor and a great presence. He would open the second act, and he would sing that song. And the Fisher Theater, seating three thousand people, there would be no applause. I mean, none.

Finally, they had the idea that they take the song I had, “Now I Have Everything,” and have Bert sing a variation on it at the top of act two: a different lyric, a different rhythm, a different orchestration, and it would be an echo of what I, the tailor, had sung in the first act.

Bert, the first time he did that, got a huge hand at the end. Then a voice was heard from within the cavernous audience at the Fisher; a woman said to her husband, Morris, didn’t the little tailor sing that in the first act?

Now, I did not fly from Detroit to Washington. I went home to stay overnight with my parents, and then I got on a train from that area down to Washington.

Parenthetically, it was the first anniversary of the Martin Luther King “I Have a Dream” speech, and all these Black families with picnic baskets were getting on the train. It was extremely moving every time we stopped in these little towns.

Then we got to Washington and we got rave reviews.

twi-ny: Was “Miracles” added because you lost your song?

ap: Evidently Bert, on the plane from Detroit to Washington, which I wasn’t on, came up to the assistant to Jerry, a fine director by the name of Richard Altman, and he said, Would you get them to write another song for Austin? Altman took that to Sheldon Harnick; it was the days of the Gideon Bible, so they landed in Washington and Sheldon went right to the Gideon Bible. And overnight he wrote “Miracle of Miracles.”

twi-ny: What a song!

ap: Yeah, it’s a wonderful song, but it was during the week that Jerry and I weren’t speaking.

twi-ny: Why not?

ap: He gave me a note just before a Wednesday matinee — he was giving angry notes to everybody because the show was falling apart — but he took me aside, and when Jerry took you aside, it was reason to tremble.

He gave me a very insulting note and I started crying and went up to the dressing room with Bert Convy and Joe Ponazecki who were playing the other grooms. Altman came in and said, What’s the matter with Austin?

Bert and Joe said, We have no idea.

I said, You tell Jerry he’s not to speak to me for a week.

A peak of my maturity. So we didn’t talk for a week. During that week we had to rehearse the new song, and that was very tense. Altman had the accompanist play it. We were in a little room with the wonderful Joanna Merlin, who we recently lost; she was playing Tzeitel.

He said, Okay, show me what you got, if you have any impulses about your gestures.

I did some inept shit and he said, Well, I guess I’ll have to do it myself.

And on the spot he thought of all the gestures in the song, which remained in Fiddler for the next thirty years.

It was a Tuesday night and we’re in Washington. I come offstage at almost the end of the show with Joanna, and Hal Prince, the producer, is in the wings.

He comes up to me and says, I’d like to buy you a drink tonight at the Willard Hotel, which we were staying in, in the days when the Willard Hotel didn’t have anything to live down.

[ed. note: A 1995 article in the Detroit Free Press about the closing of the hotel opens, “For more years than its neighbors care to remember, the Willard Hotel has been a magnet for prostitutes, pimps, and drug addicts.”]

I thought, Okay, I’m being fired.

You know what? The monologue in my head was, I don’t want to be in this loser show. Go ahead, Hal. Fire me. That was my inner monologue.

I got all dressed up and I went down to the bar. I thought, If I’m going out, I’m going out in style. All the actors were at the bar. Hal led me to the furthest table away from the bar.

I thought, Oh, I’m totally being fired. He said, What are you drinking? I said, Jack Daniel’s on the rocks. He bought me a triple. I thought, Okay, all right. Go ahead.

Then he said, Now, Austin, what’s happened to your performance?

I said, I don’t know what you’re talking about.

I was being ridiculous.

He said, I don’t have all night, Austin. Can we cut to the chase? It’s Jerry, right?

The next day being a Wednesday, we had a matinee. He said, All I’m watching onstage now is that you’re mad at Jerry and it’s got you all uptight. You were good in Detroit and now you’re no good at all. I’m coming to the matinee tomorrow, and I’m going to look in on your big scene. If I get the feeling you’re thinking about Jerry, I’m going to be really mad.

The next afternoon, I really began to come together again, then even more Wednesday night. Then, on Thursday, we were rehearsing; there were a whole lot of little things that Jerry was working on. Right at the end of the rehearsal, Jerry said to the cast, Everybody go out in the house. Austin has a new song coming in tonight and he needs to hear it with the orchestra.

So I sang it in front of the cast. The whole cast came bounding up on the stage after I sang it and they say, You son of a bitch, we’re just about to open after all this and you suddenly get the best song in the show.

I mean, fourteen songs are the best song in the show.

But it’s awfully good. Jerry came up on the stage and said, It’s a great song. You do it wonderfully.

And we never had a cross word again in his whole life.

We had five previews. Jerry had been working on a big number for the second act, because the word was when the first act was finally pulling together, you have all these great songs in the first act, but you need a big number in the second act.

All through the last part of Detroit and all through Washington, we would rehearse that number, which is to the song “Anatevka,” but it was a more upbeat tempo.

It took place at noon in the marketplace, with everybody hawking their wares; it was breathtaking. We didn’t put it in in Washington, so we’re going to put it in the first preview in New York.

On the Tuesday afternoon after we got back, we did the number in a little rehearsal hall on Eighth Avenue for the creatives, and everybody was excited. We took a little break, and Jerry came back and announced to everybody, You know what, we’re not going to use this number.

We all thought, Has he finally lost his mind? He said, I saw it in Washington last week up through Friday night. Then he went home for the weekend to his place up at Snedens Landing.

He said, I was thinking, while we weren’t looking, the second act solved itself. It’s a very original second act. It ends on a note that’s not tragic but very, very sad.

It’s so unlike the first act; there's no show like this. In the meantime, throughout the Washington run, people would come to the stage door to crowd around Zero [Mostel, who played Tevye], and he would announce to them, This is the worst second act in the history of show business!

We did our first of the very few previews, and a stage manager, Tom, a guy who had also been the stage manager of Oh, Dad — and he was also the stage manager for Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl — he came backstage after it, and he said to me, Where’s the second act problem? It works so beautifully. And I thought, That Jerry Robbins, G-d, no other director-choreographer I can think of would have done what he did.

Austin Pendleton played the elderly Professor in Life Sucks. (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

twi-ny: He pulled it off.

ap: Tom was saying, G-d, the second act is just haunting. It just really works.

Then we played our previews, and those were the days when the critics came opening night. We had a good opening night, and we went to the Rainbow Room for the party; we were all so relieved that finally the ship is in the harbor and so forth.

A bunch of us were at one of the tables and we saw a guy anxiously hurrying across the room with a newspaper. And we called him over and said, What are you doing?

He said, with a very worried expression, I’m taking the Walter Kerr review to Mr. Robbins.

Well, that place emptied. I remember pushing on the elevator button to get the hell out of there.

The next day, which was a matinee day, being a Wednesday, we were at the Imperial Theatre, where the stage door is at the rear rather than the front, and I read that review the next morning, the Walter Kerr review. It wasn’t exactly awful, but it was utterly dismissive.

[ed. note: Among other things, Kerr wrote, “I think it might be an altogether charming musical if only the people of Anatevka did not pause every now and again to give their regards to Broadway with remembrances to Herald Square.”]

I thought, Well, that’s it. We have maybe about three weeks left. I came in the dressing room and Joe Ponazecki was there, and Bert comes around; he’d been out front.

He said, Have you guys been out front? The line’s around the block.

The Kerr was in the Herald Tribune at that time. The Times review was favorable; “respectful” is a good word for it. Not like for South Pacific or My Fair Lady or anything like that. It was like, It’s a fine, honest musical.

twi-ny: So was it word of mouth that created that?

ap: It must have been. And then of course it just continued.

I had the treat of acting in it for over a year, including the out-of-town tryouts, with Zero Mostel, who was a wild man.

twi-ny: I can’t imagine. My parents saw it with Herschel Bernardi.

ap: He was lovely in it.

twi-ny: So it was a blast working with Zero? He was just unpredictable, I’m imagining.

ap: “Unpredictable” is a gentle word for it. He was anarchy. But he liberated me as an actor. I had already been studying with Uta Hagen for a while, and she once used this unforgettable phrase with me. She was encouraging, very encouraging. But one day after a scene, she said, Austin, you have a constipating sense of truth.

By which she meant, and she was right. You’re always checking on your truthfulness. You just have to let go was what she was saying. She was totally right; she always was. I must say that Zero took care of that. It was a wonderful year. I always treasured it.

The reason I left . . . I was having a drink with Hal in some bar, probably the Foundry, and he said, Are you going to renew after your contract? I said, Well, no, I’ve been asked to come home after my contract is up in August and direct my mother in a production of The Glass Menagerie. And Hal said, Okay, I don’t want to be remembered as the person who got in the way of that.

Then he made me a wonderful offer. He said, Okay, you can do that, and good luck with your mom, et cetera. After a few months, you can reenter the cast.

By this point, it was clear the show was going to run forever. While I was in Ohio, I thought, You know what? I think I want to move on. So I came back and I didn’t get any employment for quite a while.

I ran into a director friend of mine and he said, Enjoy this time. Something’s going to come along. Just enjoy this time.

I remember the sidewalk we were standing on when he said that.

And I did. And then I finally got a job.

twi-ny: Years later, I saw The Glass Menagerie you directed for Ruth Stage. It was a splendid version.

ap: Yes, right. Ginger Grace played Amanda. It’s such a beautiful play. Over the years, I got to know Tennessee Williams.

twi-ny: I wasn’t going to bring it up, but you’re all over Tennessee Williams, acting, directing.

ap: He was outrageous. He was outrageously funny. I would quote him, but I think it would be inappropriate here.

twi-ny: It’s okay. You can say whatever you want.

ap: Well, okay. I met him in 1981; he came to the out-of-town opening of The Little Foxes in Fort Lauderdale. He and his entourage came up from Key West, which is under an hour drive.

I’d never met him. In the community theater that I grew up around, they were always doing his plays. So I was obsessed with him. I still think he’s one of the five or six greatest ever.

I also think that his late plays . . . The word on him was that he went into decline after The Night of the Iguana. I don’t agree with that at all. One of the plays in those last twenty years was a play called A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur.

twi-ny: I saw a version you directed a few years ago.

ap: Yeah. There are four women in it. I’d noticed when it was playing at Spoleto, in South Carolina, that the two most important of the four women roles were played by Shirley Knight and Jan Miner.

I noticed that when it opened off Broadway for a limited engagement [in 1979], it was Shirley Knight and Peg Murray, who, by coincidence, had been Jo Van Fleet's understudy. I wondered why; I didn't get a chance to see it. [Van Fleet was in Oh Dad with Pendleton and Barbara Harris.]

So here I am, at the opening-night party in Fort Lauderdale for The Little Foxes, the one that I directed. The producer and I weren’t getting along. He took over a country club in Fort Lauderdale for the party. I entered and headed toward the head table that had him and Elizabeth and Maureen and some of the donors. The waiter, with evident embarrassment, directed me to a whole other table. I could tell the waiter was embarrassed; he was a sweet guy.

It was a table across the room with Tennessee and his entourage. I approached, and they all stood up and applauded me. Elizabeth and Maureen came over and they had an outrageous reunion with Tennessee, and then they made their way back to the head table.

So there I am with Tennessee Williams. He was looking at me as if I had to start the conversation. I said, Well, I’m so glad to meet you for a lot of reasons. One of them is I want to tell you that I’ve so admired all your recent plays (because every day they would write in the papers and in the magazines that he’s in decline).

I said, I’m a great admirer of the plays you’ve written these past twenty years.

[ed. note: Pendleton delivers all the below Tennessee lines with a southern, Williams-esque flourish.]

He said, Give me an example.

I said, Well, A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur.

He said, Do you know why Miss Jan Miner did not come to New York with the production?

He said, Because Miss Shirley Knight is a cunt.

That was the first exchange we ever had. I told him I had to go in the next room and call up Lillian Hellman, the writer of The Little Foxes.

He said, Tell her for me, she’s going to make a mint in this production. Tell her to send some of it to me. Tell her I’m a starving playwright in rags and tatters.

I did, and she got a hoot out of that.

I came back and I said, She said the check is in the mail.

He made an outrageous gesture of wiping his brow with relief.

Austin Pendleton and Carrie Nye in “Tennessee Williams: A Celebration” (photo by Jessica Katz / courtesy Williamstown Theatre Festival)

A year and a half later, up at Williamstown, the artistic director there, Mr. Psacharopoulos, put on a six-hour show called “Tennessee Williams: A Celebration.” You had to see it on a Thursday night and then a Friday night or at a matinee and then an evening.

It was scenes from almost everything Tennessee ever wrote. And his friend Carrie Nye, who was a wonderful actress, was playing the Blanche scenes. I was onstage in all the scenes, even the ones I wasn’t in. I was in the background because I had written them.

At the dress rehearsal, which did not have an audience, the show was so complicated. Carrie was playing, quite beautifully, probably the most painful scene in Streetcar, which is the breakup with Mitch.

It was just Tennessee and his companion, the designers, and Nikos. The more painful the scene became, the more Tennessee would cackle. His “cackle” — there’s no other word for it.

Finally, Carrie and I just stopped the scene and said, Tennessee, shut up.

He called back from the darkened auditorium, Blanche is the funniest character I ever wrote.

Then I had a perception. I suddenly realized, that’s why that character works. A fair amount of the time he makes her ridiculous so that then when it’s really painful, you’re shattered because you don’t feel you’ve been manipulated. He doesn’t sentimentalize.

During that time, Carrie was staying at the Williams Inn. He would call her at six in the morning. She had three or four twelve-hour days of tech because it was two three-hour shows.

She would pick up the phone and he would say, Carrie Nye, Shep Huntleigh.

Huntleigh is the offstage character from Streetcar [Blanche’s former suitor who she thinks is going to save her]. Carrie would tell me how he would go on and on and on.

We had scenes from every play he ever wrote. He would go, Why is Chance Wayne [from Sweet Bird of Youth] being played by a fairy?

Chance Wayne was in fact being played by, like, the straightest actor [Daniel Hugh Kelly] there ever was.

Tennessee would just ramble on and on and she could not get him off the phone. We had two opening nights, two nights in a row. There was a restaurant in Williamstown at that time called the River House where the opening parties were.

There were small rooms to the side. My parents were there each night, in a little room to the side. And it happened to be my father’s birthday. Tennessee would come over. He would kiss my mother’s hand. He would wish my father a happy birthday.

He had said to me when we were in rehearsal for this, I very much admire your performance.

He was very courteous.

He said, If I may make one observation.

I said, Of course.

He said, You’re too fat to play me. I was a very slender young man. So if you would come every day to the spa at the Williams Inn for two hours. . . .

I went to Nikos, who said, A.C. — which are my first two initials — A.C., if you spent two hours every day in the Williams Inn spa, you will no longer physically exist.

At each of the two opening nights, the cast would all bow. There were fifty of us.

[ed. note: In addition to Nye and Pendleton, the performers included Karen Allen, Michael Ontkean, Maria Tucci, Dwight Schultz, Katherine Helmond, James Naughton, George Morfogen, Steven Skybell, and Roberta Maxwell.]

Then we would all go out in the auditorium and Tennessee would come up on the stage. And, of course, each night he got a prolonged standing ovation, for his entire life. It was very, very moving.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I told Austin that I had to leave for the hockey game, and he seemed a little disappointed — as was I, particularly later that night after seeing the Rangers get blown out by the Winnipeg Jets.

I told him that I look forward to whatever he is doing next, that sometimes it feels like all I do is see shows that he is involved in.

I’ll try to slow down, he said.

No, no, no, never, I replied.

I love both of your interviews with Austin. I also love Austin too, thank you for posting these.