jeff ross’s origin story: is that a banana in your pocket?

Jeff Ross makes a triumphant Broadway debut with his one-man show, Take a Banana for the Ride (photo by Emilio Madrid)

At the end of Jeff Ross’s hilarious, deeply touching solo Broadway show, Take a Banana for the Ride, at the Nederlander Theatre through September 28, the comedian known as the Roastmaster General asks, as a kind of encore, if there is anyone in the audience going through a tough time. The night I went, about a dozen or so people stood up, and Ross, microphone in hand, approached them one at a time, giving each a little zinger along with an organic banana.

It reminded me of the part of the Jewish service when the rabbi asks anyone with a sick or ailing friend or relative to stand and call out that person’s name; it’s known as the Mi Sheberach, or prayer for the ill. As a child — and even now, as an adult — I never wanted to be one of those standing.

But I stood up at the Nederlander.

As I’ve noted in previous posts, I lost my job of twenty years in the spring, and I have just had knee surgery, so I’ve been walking with a cane. I’m not looking for sympathy, and I don’t need anyone saying a Mi Sheberach for me. I’m fine.

However, I desperately wanted Ross to roast me — and I wanted a banana.

The show gets its title from something Ross’s beloved maternal grandfather, Pop Jack, used to tell him when Ross, who was raised in the Newark suburbs, was heading into New York City for a comedy gig. “Champ, take a banana for the ride,” Pop Jack would say. “You never know what’s going to happen; you might get stuck in traffic, you might need some potassium, you might need it for low blood sugar, and in a pinch you could use it as a dildo. If you get sad, turn it sideways, it’ll remind you to smile.”

Ross asked me how I was doing, mentioned the cane, which I lifted for everyone to see, and then gave me a banana and some important advice: “Don’t deep throat it.”

Here’s what I actually did with it:

The play hit me in the gut as well as the funny bone. I imagine that many Jews from the tristate area have similar stories, but Ross’s life connects with mine across numerous coincidences.

We were born only a few years apart in the 1960s. His family business was a catering operation known as Clinton Manor; my family business was a tire and auto repair shop in Brooklyn. When we left Brooklyn for the South Shore of Long Island, we moved into a house on Clinton St. (When I met the woman who would become my wife, she was living on Clinton St. in Brooklyn.)

Ross, whose real last name is Lifschultz, lost both his parents when he was a teenager; I lost my father when I was twenty-two and he was forty-seven.

Both of our mothers were well endowed. Ross gleefully discloses, “My mom had huge tits. Like gigantic, and a great sense of humor. So my dad would try to make her laugh just so her tits would bounce up and down. We didn’t have cable back then.” Fortunately, we did have cable.

Ross went to film school, as did I. During college, I was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, a chronic intestinal disorder, while Ross, at his first colonoscopy in his late fifties, was found to have a stage 3 tumor. “So last summer, I had seven inches of my colon removed. Now I have a semicolon,” he says.

His father liked to gamble in Atlantic City; my father and I had a memorable trip to AC, just the two of us. His father met Don Rickles there; my father took me and my brother to see Rickles at Westbury Music Fair, then charmed a security guard to allow us backstage to be insulted by the comic genius, who called me a hockey puck.

Ross’s uncle Murray and my great-uncle Jack were both WWII heroes.

The show is smoothly directed by Broadway first-timer Stephen Kessler, not to be confused with my cousin Stephen Kessler of the Upper East Side.

Ross has dreams where his mother comes to him; I have dreams where my father comes to me.

In a beautiful segment, he shares some love letters that his father wrote to his mother when he was in junior college; he recently found them in a box. Two years ago, I found a box of love letters that my mother wrote to my father when he was stationed at Fort Dix; I shared them here.

There are also plenty of differences. I was not bullied as a child; Ross was so picked on that he took up karate and became, at ten and a half, the second youngest black belt in the United States. “They called me Kosher Kai. I put the Jew in Jujitsu,” he beams.

I shaved my head because I was naturally losing my hair anyway in my thirties. Ross lost nearly all the hair on his body after contracting alopecia when he was around fifty. “Who’s gonna date somebody that looks like a Jeff Bezos blow-up doll?” he asks. “I know I look like Bruce Willis if his trainer also had dementia. I look like Vin Diesel if he were neither Fast nor Furious.”

No topic is off limits for Ross’s jokes. Upon acquiring two German shepherds during the pandemic, he boasts, “I named them Ausch and Schwitz. I love them, but I still kick ’em once a day for every Jewish person that died in the Holocaust.”

Ross also points out that his first time in front of a microphone was when he was nineteen, delivering his father’s eulogy. I recently detailed how I had to have a friend read the eulogy I wrote for my father.

Jeff Ross explores his life in hilarious and poignant one-man Broadway show (photo by Emilio Madrid)

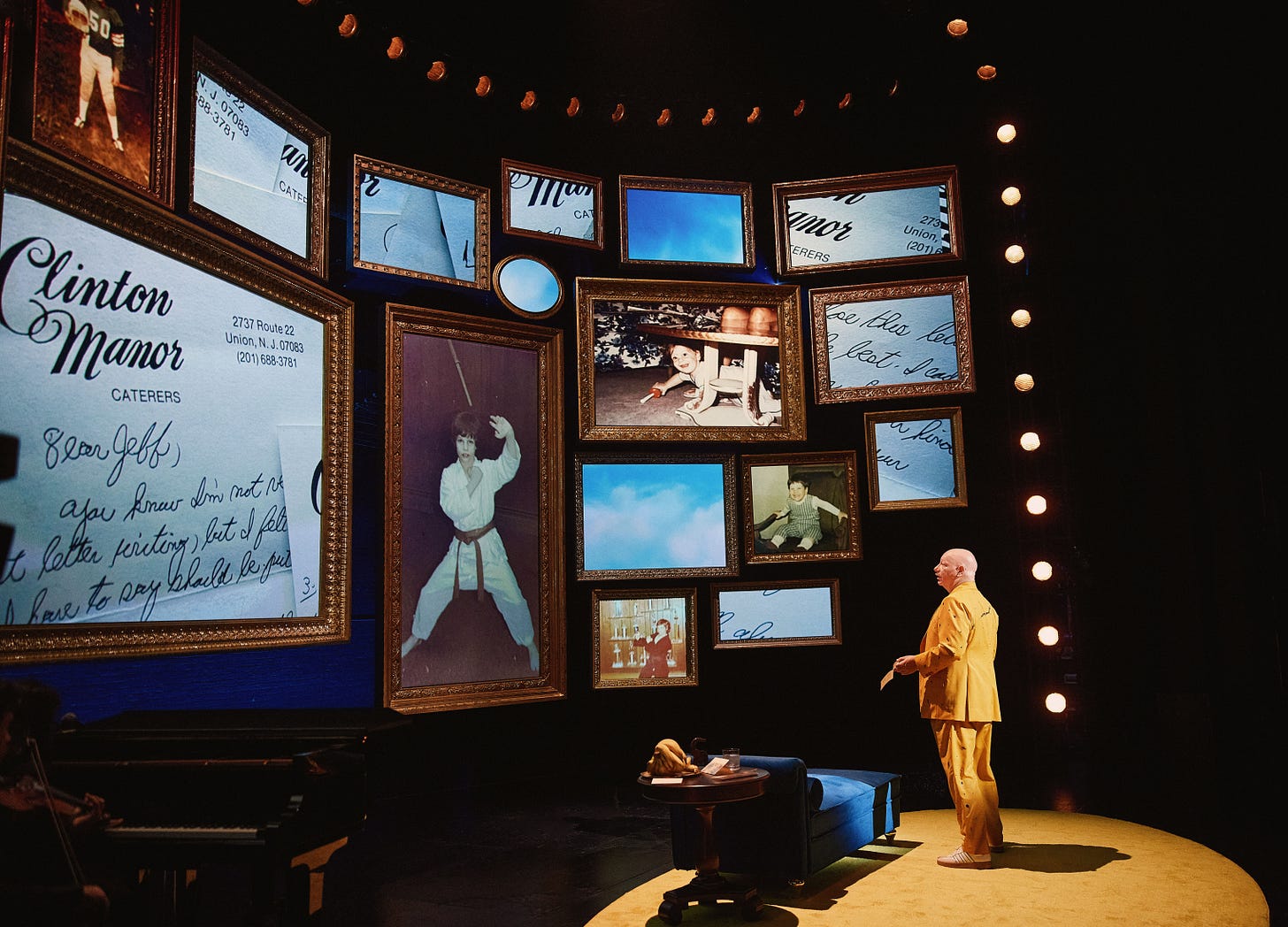

For ninety minutes, Ross opens up about his personal life, highlights special moments from his career, and sings — poorly, but why not? He talks about his close friendships with the late Bob Saget, Gilbert Gottfried, and Norm Macdonald. He is accompanied by pianist Asher Denburg and violinist Felix Herbst; behind him is a curved wall of twenty-four different-sized monitors projecting home movies, family photos, clips from his live performances and talk-show appearances, and other ephemera. (The welcoming set, by Beowulf Boritt, also features a comfy couch and small table; the projections are by Stefania Bulbarella.)

As Roastmaster General at the Friars Club and for Comedy Central and Netflix, he has skewered such stars as Justin Bieber, Pamela Anderson, Alec Baldwin, Rob Lowe, Roseanne Barr, Charlie Sheen, Tom Brady, William Shatner, and Donald Trump. His comedy specials include The Burn, No Offense, and Patriot Act. In 2009, he published I Only Roast the Ones I Love: Busting Balls without Burning Bridges. He still knows what to do with nunchucks.

As with me, being Jewish is central to his being, and not necessarily in a religious way. One of the songs his great-grandma Rosie would sing to him at bedtime and that he has never forgotten is “Don’t Fuck with the Jews,” which is my new mantra. “Don’t fuck with the Jews,” he warbles. “Unless you want your ego badly bruised. / Never again. Fuck with the Jews.”

Ross is innately comfortable onstage, an amiable presence despite his ready arsenal of sharp barbs; wearing yellow pants, sneakers, and a yellow blazer over a black-and-white Gilbert Gottfried T-shirt, he says near the beginning, “If you’re going through anything intense in your life right now . . . you’re in the right place. You are. I’ve become really good at cheering people up. . . . I learned early on that comedy isn’t just in my blood; it’s my superpower. And this is my origin story.”

Near the conclusion, he announces, “I feel like the luckiest motherfucker in the world right now.”

Walking out of the Nederlander Theatre with an organic banana in my pocket and a jaunt in my limp, so did I.

[You can follow Mark Rifkin and This Week in New York every day here.]

This is an amazing, perfectly balanced critique and personal reminiscence--well done all around. By the way, I also saw Rickles at Westbury (and earlier in Atlantic City with my father).