Six women form a consciousness-raising group in 1970 Ohio in Bess Wohl’s Liberation (photo by Joan Marcus)

March 8 was International Women’s Day (IWD). First held in 1911, IWD is, according to its mission statement, “a specific day dedicated to the advancement of women worldwide [that] celebrates the social, economic, cultural, and political achievements of women. The day also marks a call to action for accelerating gender equality.”

You might not have known about it because Google removed both IWD and Women’s History Month from its calendar; meanwhile, federal agencies have “paused” celebrations of both those events, along with Women’s Equality Day, Juneteenth, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Holocaust Day / Days of Remembrance, and others because they do not fit their anti-DEI agenda. My fiercely liberal mother, who taught me about such political sheroes as Shirley Chisholm, Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, and Elizabeth Holtzman, would be furious if she were still alive.

The night before, on March 7, my wife and I saw one of the best shows of the year, Bess Wohl’s dazzling Liberation: A Memory Play About Things I Don’t Remember, in which the playwright reimagines her mother’s 1970s consciousness-raising (CR) women’s group. The women meet in a rec center basement in Ohio to discuss the role of women in society, how it impacts their lives individually and what they can do to help change the status quo publicly.

The time shifts between the early 1970s and the present, when Wohl, lovingly portrayed by Susannah Flood, interviews surviving members of the group and talks directly to the audience about what is happening today. Wohl is one of the country’s premier playwrights, having previously staged the stirring Small Mouth Sounds, Continuity, Make Believe, Grand Horizons, and Camp Siegfried in a remarkably fertile seven-year period through 2022.

Earlier on Friday, the New York Times published a story titled “These Words Are Disappearing in the New Trump Administration,” detailing a list of approximately two hundreds words, phrases, and acronyms that federal agencies have been tasked with limiting or outright avoiding in official documents. Among those that might end up missing in action are activists, bias, discrimination, equal opportunity, (in)equality, female(s), feminism, gender, injustice, minorities, prejudice, privilege, race, racism, sex, trauma, victim, and women.

Yes, women.

Much of the language in Liberation would have to be redacted if it ever came to the Kennedy Center, which of course is extremely unlikely anyway.

The play, luminously directed by Whitney White (soft, Jaja’s African Hair Braiding), begins with Wohl greeting the audience. “Hi. Is everyone — is everyone good? Comfortable? Snacks unwrapped?” she asks. “Hello. Hi. Welcome. They took your phones. Are we okay? Are we okay. I promise you’ll get them out of that pouch at the end of this — and — speaking of — how long is this going to take, right? I know that’s all anyone really wants to know: the running time.”

On the way into the Roundabout’s downstairs Laura Pels Theatre, ticket holders had to turn off their phones and have them locked in a yondr pouch so they cannot access them during the show. The main reason is to respect the actors’ privacy during a spectacular nude scene that kicks off the second act, but it also helps put everyone in a 1970s mind-set, before there were cellphones and other technological distractions. Cleverly, Wohl does not tell us the running time, since the liberation battle is still being fought more than half a century after the meetings ended.

Wohl’s mother, Lizzie (Flood), is an investigative journalist reduced to covering weddings and obituaries — “which in a way are the same thing!” she notes, as if marriage and death are the same thing. Describing the origins of the theatrical piece, Wohl says, “This is a play about my mother. For my mother. Who recently . . . Who’s not here anymore. And so it’s about her, and her friends, her beautiful friends — and a thing — this is important — a thing they tried very hard to do. No, a thing that they did, that they unquestionably did — so why does it feel somehow like it’s all slipping away? And how do we get it back —”

Lizzie has put up flyers to form an initially ill-defined CR group. Lizzie is joined by five unique women: Margie (Tony nominee and Obie winner Betsy Aidem) is an empty-nest housewife with an oafish husband who she dreams about stabbing to death. Susie Hurricane (Adina Verson) is a radical punk who recently moved to Ohio for a job that fell through and is now living in her car. Celeste (Kristolyn Lloyd) is a Black intellectual who has had to return to Chicago, where she was born, to take care of her ailing mother. Isidora (Irene Sofia Lucio) is an Italian filmmaker who is in a green-card marriage. And Dora (Audrey Corsa) is a Barbie-esque woman who is furious that she has been passed over for a promotion that instead went to an ill-equipped man.

A group of women bare their souls and more in powerful and involving new play (photo by Joan Marcus)

Each woman has been held back because of her gender.

“I’ve never paid a bill. I don’t have a bank account. I can’t drive,” Margie explains.

“Like, I don’t even know what to say anymore. Women are human beings. If you don’t believe that, at this point, I don’t know how I can help you. It feels kind of like we’re shitting into the wind,” Susie declares.

“I’m for the end of oppression — economic, class-based, sex-based, race-based — I reject pedestals, I reject walking ten paces behind, to be recognized as human, levelly human, that is what I want,” Celeste demands.

“I think women deserve a turn,” Isidora, who previously worked with SNCC, avows.

“Um, I um, I actually thought this was a knitting circle? I brought my knitting?” Dora admits, although she ultimately decides to stay.

Later, a mother named Joanne (Kayla Davion) tells them, “This is the thing about you radical women — you get so serious about everything.”

In addition, there is one man, Bill (Charlie Thurston), who is attracted to Lizzie and serves as a catalyst for conversations about the necessity and the value of a man in a woman’s life.

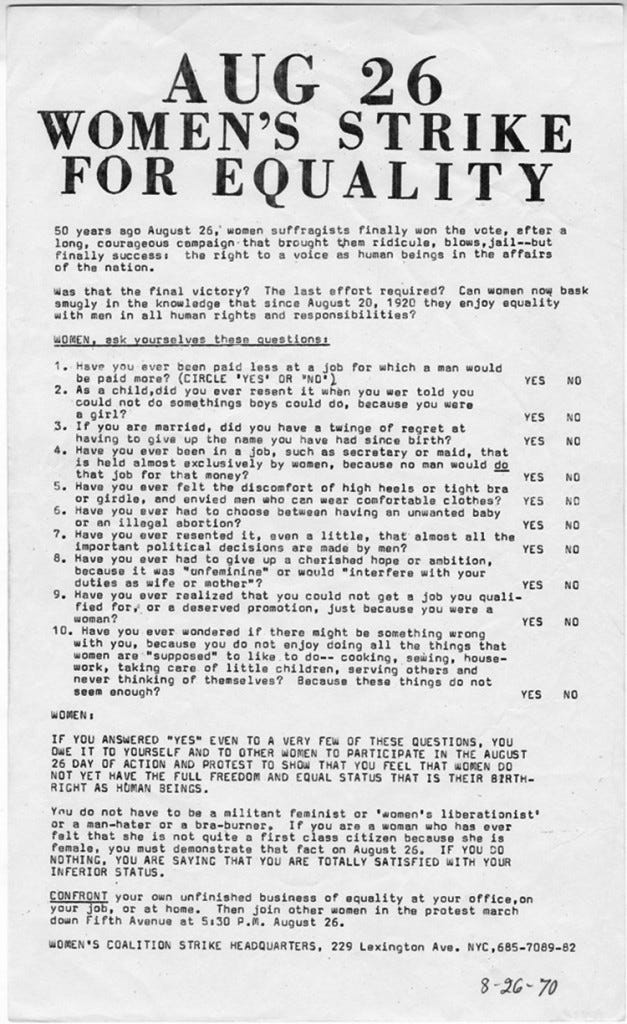

The group discusses Betty Friedan, childbirth as the basis for inequality, Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, marriage and motherhood, and participating in the Women’s Strike for Equality, which asks the question “Can women now bask smugly in the knowledge that since August 20, 1920, they enjoy equality with men in all the human rights and responsibilities?”

Susie delivers a “womanifesto” that proclaims, “We define the best interests of women as the best interest of the poorest, most insulted, most abused woman on earth. She is Everywoman: ugly, dumb, dumb broad, dumb cunt, dumb bitch, nag, whore, fucking and breeding machine, mother of us all. Until Everywoman is free, no woman will be free. When her beauty and knowledge is revealed and seen, the new day will be at hand.”

That concept of the Everywoman takes center stage at the start of the second act. Lizzie, Margie, Susie, Celeste, Isidora, and Dora remove their clothing (the period costumes are by Qween Jean) and sit in the usual semicircle of folding chairs, Cha See’s gymnasium lighting keeping them brightly lit so there’s nowhere to hide. “The idea is we all go around and say one thing we love and one thing we hate about our bodies,” Dora says, claiming she read about this in Ms. magazine.

One by one, they share intimate details — or opt not to — about their bodies, each one dealing with their nudity in a different way, choosing to proudly reveal or attempt to conceal. The overt nakedness can make the audience, especially the men, uncomfortable, confronting them with questions about their own attitudes.

Before taking off their clothes, the women in the play push a barricade in front of the door so no one at the rec center will see them, yet the performers are intrinsically aware that more than four hundred people are watching them intently in the theater, following their every word and movement. I felt like I was invading the privacy of the actors and the characters, but it’s hard to turn away because their actions and reactions help define who they are. It also is a visual reminder that every woman’s body is unique, and uniquely beautiful. The best answer, however, comes from the woman who answers that her favorite part of her body is her brain.

Touché.

Lizzie’s generation is the one that fought for women’s rights and helped get Roe v. Wade passed in 1973 but strived for so much more. Wohl’s generation is the one that has seen Roe overturned, along with so many other antidiscrimination and reproductive health laws. It seems now that even voting is on the table, as the proposed SAVE Act dictates that a voter’s birth certificate name must match the one on their current identification, which could purge from the rolls married women who have changed their last name to their husband’s if they don’t have the proper paperwork on hand.

Early on, Lizzie says, “My idea is, well, no, it’s not mine, obviously — but the general concept is — if we raise our consciousness, increase our understanding of the oppression and the sources of oppression in our own lives — personally — this is how we change the world, we raise our consciousness, we change the world.”

But more than five decades later, Wohl is trying to understand how it fell apart. She tells us, “I wanted to know, I needed to know — what went wrong? Because, I mean, look around. Look at what’s happening in the world right now — what is happening and can someone please explain it to me and how do I explain it to my children — and so I thought if I could just talk to these women —”

Wohl began writing Liberation during the first Trump administration but did not complete it until after the 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which sent abortion rights to the states.

It’s unconscionable that the fight is still going on after all these years.

In the play, Dora sums it up best when she relates what she told her boss after he gave the promotion she felt she had earned to a man.

“The only thing Ray has that I don’t is a penis!”

[Liberation continues at the Laura Pels Theatre through April 6. You can follow Mark Rifkin and This Week in New York every day here.]

I saw this wonderful play with a group of women, and we all loved it. I really enjoyed reading your review - there was so much in it that I need and WANT to see it again. Thank you for adding the flyer for the Women's Strike for Equality. It's incredible to read that! We were 7 years old - our poor mothers! BTW - your mom sounds like she was amazing! Did you know that when we were in kindergarten, girls were not allowed to wear pants yet? I think that changed in 1970-ish.