All are welcome at La MaMa for Exagoge (photo by Richard Termine)

I was brought up having two seders, one on each of the first two nights of Passover, or Pesach, the Hebrew name for the spring holiday. The seder, which means “order,” is the traditional gathering during which Jews around the world remember the Exodus, telling the story of how the Israelites escaped slavery in Egypt under the leadership of Moses, who might have been the star attraction but whose name is not mentioned once in the Haggadah, the book we read at the seder.

Imagine what The Ten Commandments would have been without Charlton Heston as Moses.

This year I attended three seders; on April 22 we went to my cousins on the Upper East Side, and on April 23 we went to dear friends in Brooklyn. We have been regulars at each seder for a bunch of years now.

On the seventh night, we got a bonus; my wife and I were at La MaMa for the world premiere of Untitled Theater Company No. 61’s brilliant Exagoge, an immersive opera-play built around an actual seder.

When I was a kid, my parents would host one night, my aunt and uncle the other. For several decades, after my father died in 1985, I led my mother’s seder. (My mother passed in 2017.) I took the responsibility pretty seriously; I did not like to skip around the Haggadah, and I preferred that everyone, including the children, pay attention. I encouraged discussion, no matter how political. I didn’t want any chometz at the table, only kosher for Passover food and drink.

However, I was not as much a stickler as my mother’s maternal grandfather; I heard tales about how he would keep doing his duty as leader even as everyone else started — and finished — eating. There he’d be, still reading the Haggadah, all by himself, into the wee hours of the morning.

American Jews tend to celebrate eight nights of Pesach, with two seders, while Israelis celebrate for seven nights, with one seder. Some Jews have an additional seder on the seventh night. According to the Velveteen Rabbi, “The seventh day of Pesach is considered to be the day when our ancestors passed through the Sea of Reeds. Each of us is called to experience the Exodus from Egypt in our own lives, and this is the day when we too experience the sea parting and our arrival on the other side. Some have the custom of celebrating a special seder on the seventh day of Pesach, commemorating the journey.”

Moses (Charlton Heston) parts the Red Sea in The Ten Commandments

The Orthodox organization Chabad explains, “Israel was commanded to observe the last day of Passover even before she knew that the Egyptians were destined to drown in the sea on this day. The Torah therefore ignores the link between the last festival day and the splitting of the sea. The essence of the celebration of this day is the song that Moses and Israel were Divinely inspired to sing on this day [Ha'azinu], a song that merited being included in the Torah, a song to which G‑d and His heavenly consorts listened.”

The essence of Exagoge is song as well. The play is a melding of opera and theatrical drama, featuring script, libretto, and direction by Edward Einhorn (The Marriage of Alice B. Toklas, The Taste of Damnation) and music by Avner Finberg. The show goes back and forth between a contemporary seder, led by family patriarch Avraham (Maxwell Zener), and scenes from an opera-in-progress written by his son, Zeke (Hershel Blatt), based on Exagōgē, the earliest known Jewish play, penned in Alexandria in the second century BCE by Ezekiel the Tragedian; the play exists only in fragments, so Zeke has expanded the narrative on his own.

The protagonists sit at a table at the back of the stage on top of a series of steps; to the left and right are two tables of four audience members each. Another eight members of the audience sit at a long table in front of the regular seats, which are arranged in standard risers. Tom Lee and Grace Needlman’s set essentially places everyone in the desert.

The show begins with Avraham explaining, “For those who have been here before, you know it is my tradition to start every seder off with a question. This year, I have been asking myself, What do we learn by repeating the same story, year after year? I suppose in some ways I am asking, What is the purpose of any repeated ritual? For me, it is renewal of my faith: faith in my traditions, in G-d, and in perseverance. And yet each time I hear it, each time it is told, it is different, because I am different.” It’s a beautiful, touching sentiment.

Exagoge napkins depict traditional seder plate (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Zeke then arrives, late, and he has brought a date without advising his father, who is not thrilled, especially when it turns out that Aliya (Meena Knowles) comes from a Muslim family. But it’s not her first seder; she quickly points out, “I’ve lived my whole life on the Upper West Side.”

Avraham guides everyone through fifteen parts of the seder, including the Kiddush, the Four Questions, the Four Children, the Ten Plagues, and the karpas, bitter herbs, matzah, Hillel sandwich, and afikoman. The guests at the tables have goblets for wine or grape juice and plates and silverware for pesadicha (kosher for Passover) tastings; the napkin is a colorful depiction of the seder plate.

Avraham asks that the door be opened for the prophet Elijah, representing hope and redemption, a symbol that has taken on greater meaning in the midst of America’s border crisis, among other current events.

When I was young, our Haggadah began with the Matzah of Hope, offering a prayer for the plight of Soviet Jews who were not permitted to practice their religion or to leave the country. Now the Matzah of Hope makes us think not only about the war in Ukraine but October 7 and its aftermath, which started when Hamas attacked Israel, leaving in its wake murdered, mutilated, raped, and brutalized men, women, and children; with Hamas continuing to refuse to release more than a hundred hostages as part of a potential cease-fire agreement, the IDF has not stopped its bombardment of Gaza, resulting in more bloodshed.

Moses (James Benjamin Rodgers) encounters the burning bush in Exagoge (photo by Richard Termine)

The Matzah of Hope also evokes the protests that are occurring on college campuses in New York City and around America; perhaps it’s no coincidence that Avraham is a professor of Jewish history at Columbia, where two nights ago pro-Palestinian protesters broke into and occupied the university’s Hamilton Hall in a siege that referenced a bewildering kaleidoscope of historical events: January 6 at the Capitol, anti–Vietnam War demonstrations, Kristallnacht — well may we ask, What is the meaning of this story?

The sections of the Exagoge seder are followed by related excerpts from Zeke’s opera, with bass Matthew Curran as Pharaoh, Reuel, and G-d, soprano Tharanga Goonetilleke as Tzipporah, a messenger, and G-d, and tenor James Benjamin Rodgers as Moses. (Tzipporah is the daughter of Reuel, also known as Jethro, a non-Jewish desert king who becomes Moses’s father-in-law.) The singers, dressed in ancient robes and sandals, hold staffs with masks on them to identify which character they are at any given moment; there are also animal puppets operated by stagehands Rebecca Jay Caplan, Yanniv Frank, and Parker Sera. The puppets were designed by Tanya Khordoc and Barry Weil of Evolve Puppets, with costumes and masks by Ramona Ponce and lighting by Federico Restrepo. The lovely score is performed by music director Mila Henry on piano, Mariana Ramírez or Andrew Beall on percussion, Sunny Sheu and Johnna Wu on violin, Sara Dudley on viola, and Paul Swensen on cello.

Thus, after Avraham says the prayer for the karpas, the green vegetable dipped in saltwater (“We eat it as a small reminder of how food was scarce, but what there was brought joy. And we dip it in the saltwater to remember the salt tears of the slaves.”), the scene shifts to the desert, where a thirsty Moses meets Tzipporah, who sings, “Every day I walk through the desert / I look for something / Something out there / I look for something / Something that’s green / Something that’s strange / Something that’s beautiful / You need water, have mine.”

After Avraham and the audience recite the Ten Plagues, the action moves back to Moses demanding that Pharaoh “go and learn,” to free the Jewish slaves, but Pharaoh refuses to bend.

Paul Robeson recorded “Go Down Moses” in 1953

At my cousins’ seder, we always sing the African American spiritual “Go Down Moses”; this year we sang it along with a recording of the most famous version, by Paul Robeson, the Black activist, actor, and vocalist who met with the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in 1943: “Oh, when Israel was in Egypt land / Let my people go! / Oppressed so hard, they could not stand / Let my people go!” (The tune also appeared in a powerful, moving scene in the classic 1941 film Sullivan’s Travels.)

Curiously, Einhorn does not include the popular Pesach song “Dayenu” and its never-ending chorus — if you listen closely, you can still hear it echoing in the wind from last week’s seders — in his illustrated Haggadah/libretto. The song of thanks translates as “It Would Have Been Enough”; maybe he ran out of time, or perhaps we now need more to get through a society in which antisemitism is ramping up yet again.

Passover is my favorite holiday, primarily because it’s an annual opportunity for family to get together, eat special food (Haroset! Gefilte fish! Downed with Manischewitz Cream Concord!), and share the story of the Exodus. I miss my mother mangling the Hebrew words of the Ten Plagues, year after year. I miss not having my siblings with me, as they both live far away. And I miss not being at the table with my aunt and uncle, who have moved to Florida. I miss discussing with them how Pesach relates to what is happening today.

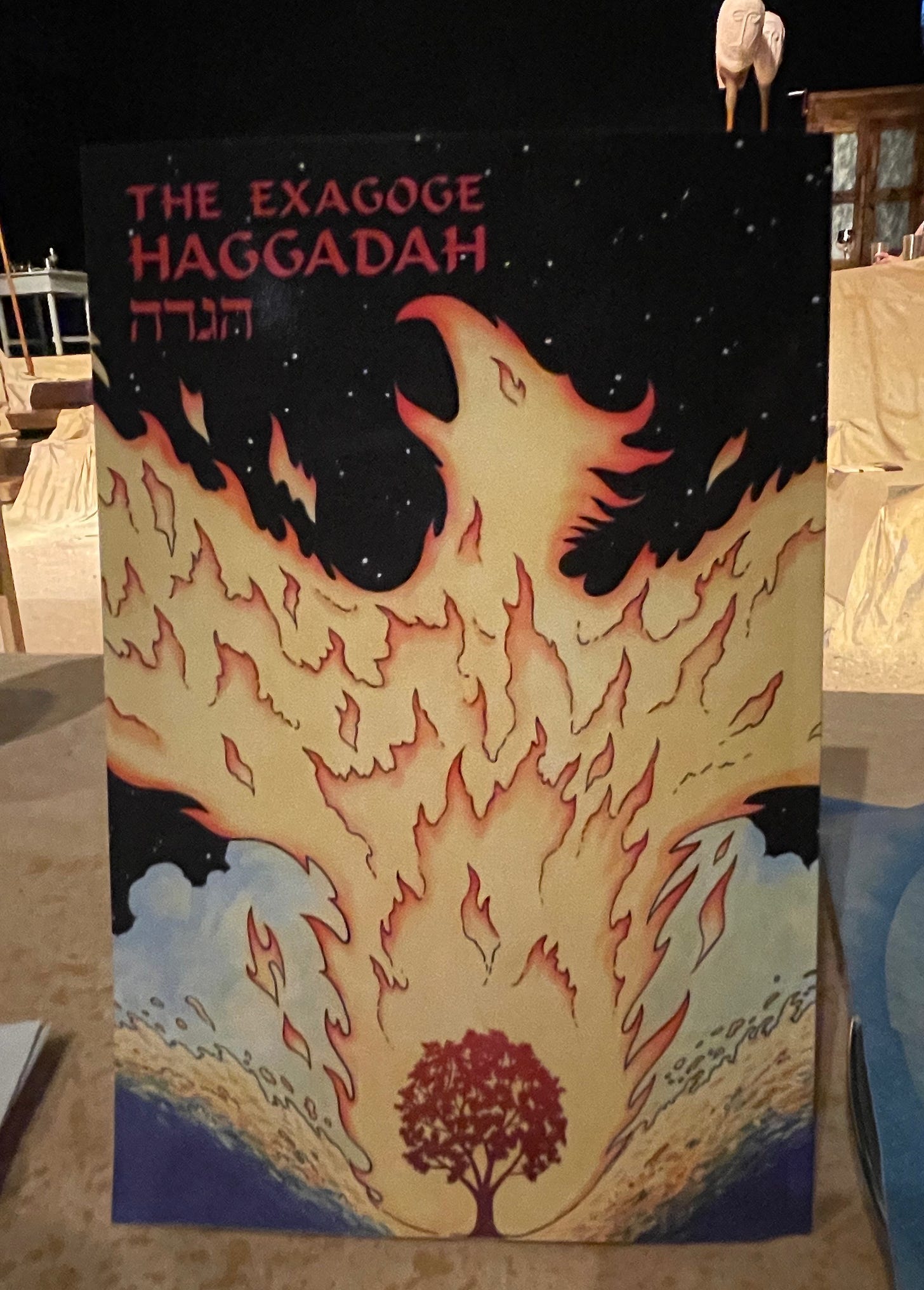

The Exagoge Haggadah serves as a libretto for a unique seder (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

I also miss the old Haggadah we used way back then, the famous Nathan Goldberg edition, although I am so impressed by the Haggadah my cousins put together themselves.

A key moment in the play occurs when Avraham notes, “As each generation reads the story, it finds a new meaning in it.” He also reminds us, “It is but a chapter of a longer narrative. And every year, for a few nights at least, we can enjoy each other’s company and make merry.”

The hundred-minute play-opera, which is expertly acted and directed, brought new meaning to me despite my familiarity with the story; it also allowed us all to make merry.

And in these difficult times, at least for one special night, that is enough.

[Exagoge continues at La MaMa through May 12; tickets are $35. You can follow Mark Rifkin and This Week in New York every day here.]

Oppression continues. So must liberation. Bill W