children's books and art: william wegman, faith ringgold, and me

William Wegman, Typical Stroke, ink on gelatin silver print, 1974 (courtesy Sperone Westwater)

Two current art exhibits in New York City sent me careening down memory lane, back to my early days in children’s book publishing, where I still work today.

Back in the early 1990s, at my second job out of college, I was a copy editor at a new but prominent company that was part of a gargantuan empire. It was essentially before the internet; I remember having to apply to my superiors to gain access to the World Wide Web, which I was granted because of my responsibilities. Even with access, though, there was no Google yet. You couldn’t just go online and get an immediate answer to any question you had about anything.

Amid movie tie-ins, branded characters, and celebrity picture books, I recall working on titles by two author-artists I knew were important but had no idea how much: William Wegman and Faith Ringgold. Putting their name in a search engine at the time did not immerse you in full accounts of their career, and the author bio on the back flap was limited to only so much information.

I was the assistant managing editor on several books by the Holyoke-born Wegman, now seventy-nine and based in New York City and Maine. (Coincidentally, I had worked with Wegman’s second wife at my first job in the industry, in the small world of book publishing.) They included two fairy-tale retellings, Little Red Riding Hood and Cinderella, featuring photos of his beloved Weimaraner, Fay Wray, and her offspring, elaborately dressed up as the beloved characters. In addition, the dogs were ingeniously shown in twisty poses that evoked letters and numbers for ABC and 1, 2, 3.

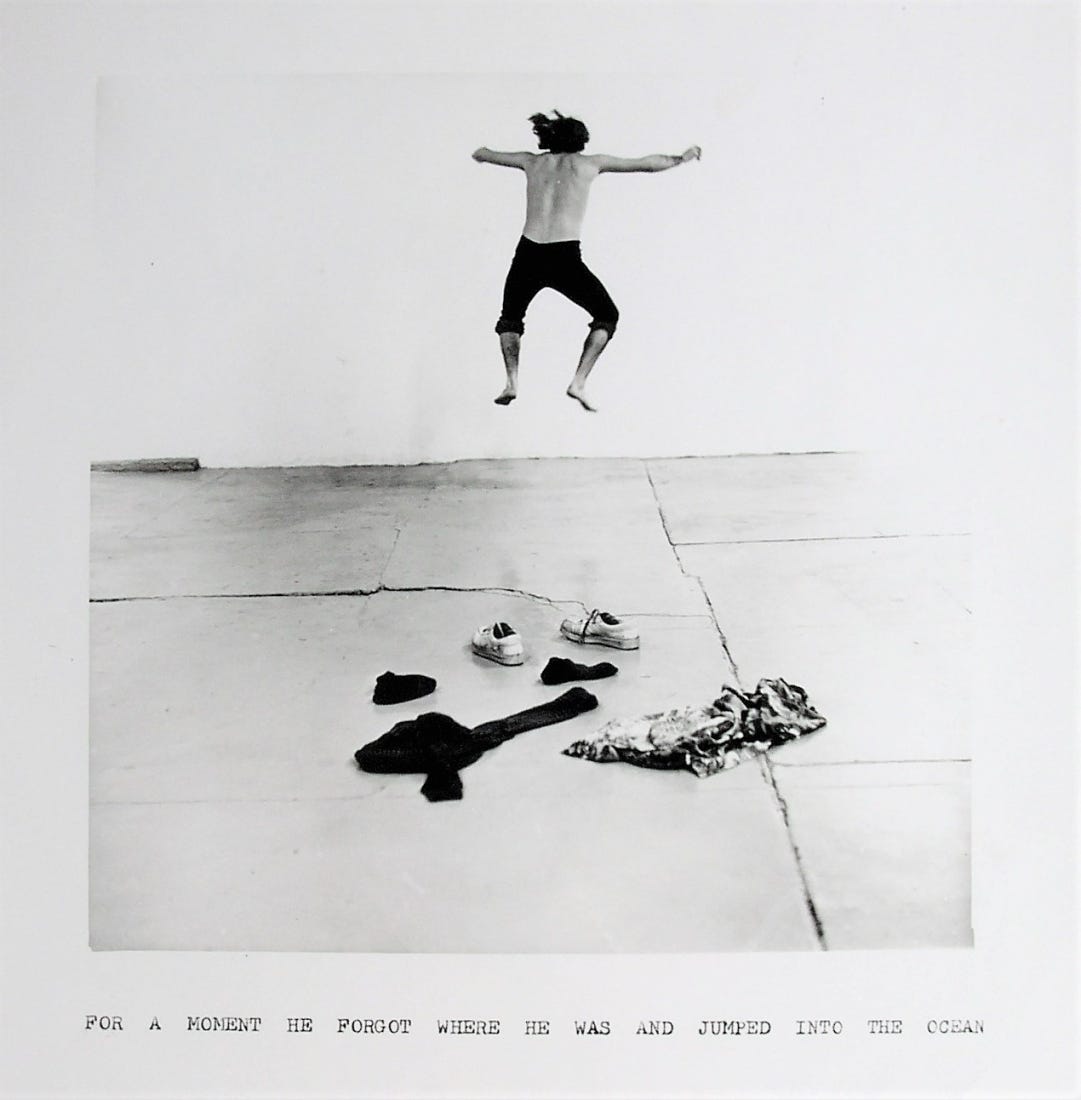

Through July 22, Sperone Westwater is hosting “Writing by Artist,” a two-floor gallery show of Wegman’s conceptual work consisting of drawings, paintings, photographs, text, and video. Many pieces combine words and images, reminiscent of pages from a picture book. In a 1972 black-and-white photo, Wegman has stripped off most of his clothing, which lies scattered on the floor, and has leaped high into the air; the typed caption at the bottom explains, “For a moment he forgot where he was and jumped into the ocean.” In one of his many low-tech videos, he less-than-perfectly recites the alphabet, the camera close in on his mouth as he carefully forms every letter, in a way presaging how he would arrange Fay Wray in the alphabet book. In another, he reads the copyright page of an old Merriam book, the company that makes the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the primary spelling source for all of publishing.

William Wegman, For a Moment He Forgot Where He Was and Jumped into the Ocean, gelatin silver print, 1972 (courtesy Sperone Westwater)

In the diptych Mistake/Correction (1975/2011), Wegman holds a telephone to his ear upside down at the left, then correctly at the right, as if fixing a typo. In a 2017 ink drawing, he actually spells his name “William Wegan.” The twenty-one-panel Please Stand By consists of text on a television screen describing technical difficulties and how to make a program: “I have to be producer, director, actor, cameraman”; “With all of our other limitations ther is not much we can do.” Because of my training, I can’t help but find mistakes in any kind of writing; artists are notoriously bad spellers, so “ther” bothered me, whether or not it was done on purpose. As Wegman points out in the same piece, “If anything goes wrong there isn’t much we can do except . . . stand by.”

However, I can’t just stand by; typos are the bane of children’s book publishing. A small mistake in a novel can be overlooked and fixed in the next printing, but the tiniest error in a picture book, even on the copyright page, can result in the terror of terrors, finished, printed books that must be pulped and reprinted. You have no idea how many times I read Wegman’s counting and alphabet books and fairy tales, making sure everything was in the right order and nothing was missing.

Faith Ringgold, Woman on a Bridge #1 of 5: Tar Beach, acrylic paint, canvas, printed fabric, ink, and thread, 1988 (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, Mr. and Mrs. Gus and Judith Leiber, 88.3620)

Just down the street from Sperone Westwater is the thrilling, revelatory “Faith Ringgold: American People,” at the New Museum through June 5. I had worked on the Harlem-born artist’s 1993 picture book, Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House, a communal celebration, through art, of a dozen Black women, from Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, and Fannie Lou Hamer to Mary McLeod Bethune, Sojourner Truth, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Spread across three glorious floors, the exhibition explodes with traditional and innovative storytelling through quilts, soft sculptures, and paintings investigating the Black experience in America, from slavery to the civil rights movement to systemic racism. Ringgold incorporates dramatic and detailed art-historical references in many of the works, reimagining familiar canvases by Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Seurat, Édouard Manet, Vincent van Gogh, and others.

She honors such ancestors and trailblazers as Tubman, Truth, Hurston, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Josephine Baker, and Richard Wright, sometimes through the guise of her fictitious alter ego, young artist Willia Marie Simone. Large-scale quilts, inspired by Tibetan thangkas, feature captioned chapters heavy with text, each work a kind of picture book unto itself, the words evoking multiple meanings.

In Jo Baker’s Birthday (1995), Ringgold writes in the seventh panel, “Beauty is wonderful, but it does not keep. It is the bloom we are all wanting to see, not the wilt. Beauty has to be recognized while it is still a bud. And though it is a pleasure to experience great beauty, the physical kind is often shallow to the touch. But Josephine is deeper than that. She has the kind of beauty that does last. Her beauty is freedom. And freedom lasts, but not without a struggle.”

The three-part Street Story Quilt (1985) uses a Harlem apartment facade to relate a trio of gripping, traumatic tales, “The Accident,” “The Fire,” and “The Homecoming,” involving poverty, war, and racism, narrated by Gracie about A.J. (Abraham Lincoln Jones). I was not searching for typos in any of the compelling handwritten text, although none stuck out regardless. As she writes in The French Collection #8: On the Beach at St. Tropez (1991), “People may want you to blame yourself as much as they blame you. But never let them convince you that you are worthy of blame. No matter how many mistakes you make. If you are trying to do something the mistakes are not your fault, though you should be man enough to pay for them.”

For the Women’s House (1972) is a mural dedicated to those incarcerated at the Correctional Institution for Women on Rikers Island, featuring a female doctor, professional basketball players, a police officer, a construction worker, and president, along with a quote from Parks: “I knew someone had to take the first step.”

Faith Ringgold, American People #18 The Flag Is Bleeding, oil on canvas, 1967 (courtesy of Faith Ringgold and ACA Galleries, New York © Faith Ringgold 1967, photo courtesy ACA Galleries, New York)

There is no text in The American People Series #18: The Flag Is Bleeding (1967), a depiction of an American flag, blood dripping from the red stripes, superimposed over a Black man, white woman, and white man linking arms; the Black man holds a knife in his left hand, his right hand over his heart, both pledging allegiance and staunching a wound.

In Dancing at the Louvre (1991), a quilt in which a Black woman and four girls dance in front of Leonardo’s La Gioconda, Simone says, “Marcia and her three little girls took me dancing at the Louvre. I thought I was taking them to see the Mona Lisa. You’ve never seen anything like this. Well, the French hadn’t either. Never mind Leonardo da Vinci and Mona Lisa, Marcia and her three girls were the show.”

Ringgold’s Caldecott-winning 1991 book, Tar Beach, gets a room of its own, highlighting the original art and text, about a young girl’s affection for the George Washington Bridge and the rooftop of the Harlem apartment house where her family lives. “Lying on the roof in the night, with the stars and skyscraper buildings all around me, made me feel rich, like I owned all that I could see,” the young girl says.

Ringgold makes us all complicit in Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro (1975-89), an installation (and, originally, performance piece) in which visitors become mourners as two bodies are laid to rest amid gorgeous wall hangings, colorful flowers, and men and women dressed in black. Although it deals specifically with drug addiction and grief, it feels even more powerful today during the #BLM movement. (In addition, Ringgold’s If a Bus Could Talk: The Story of Rosa Parks is part of “Picture the Dream: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Children's Books” at the New-York Historical Society through July 24, along with titles by numerous other authors and illustrators whose books I’ve had the privilege of working on over the years.)

Through her artwork and books, many of which can be read on the seventh floor (including Dinner at Aunt Connie’s), Ringgold, now ninety-one, has created a unique storytelling legacy through which Black people, and especially children, can see themselves, see others who look like them, and can now dance at the New Museum in front of modern masterpieces. If you can’t make it to the show, just Google her to get immersed in her remarkable world.