Harold Bloom’s order from a publishing lunch meeting more than thirty-five years ago (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

“Now is no time to think of what you do not have. Think of what you can do with what there is,” Ernest Hemingway wrote in The Old Man and the Sea, the first adult novel I ever read, when I was home sick from school one day in fourth grade.

Although the quote is not specifically about Thanksgiving, it’s one way to look at the holiday, especially if, as in my case, you have fewer close family members than ever and they are spread across the country, no longer gathering for festive meals and football as we used to do year after year.

On Thanksgiving Day, memories of those days come up, but so does an odd one that also creeps in every last Thursday of November.

In my first job in publishing, I was an administrative assistant to the editor in chief at Chelsea House, a small company with a radical history. By the time I came along, in the late 1980s, it was primarily publishing nonfiction books in series for kids. but Chelsea House also was in the midst of a grand collection of critical essays on key books, plays, poems, and authors, edited and introduced by Harold Bloom.

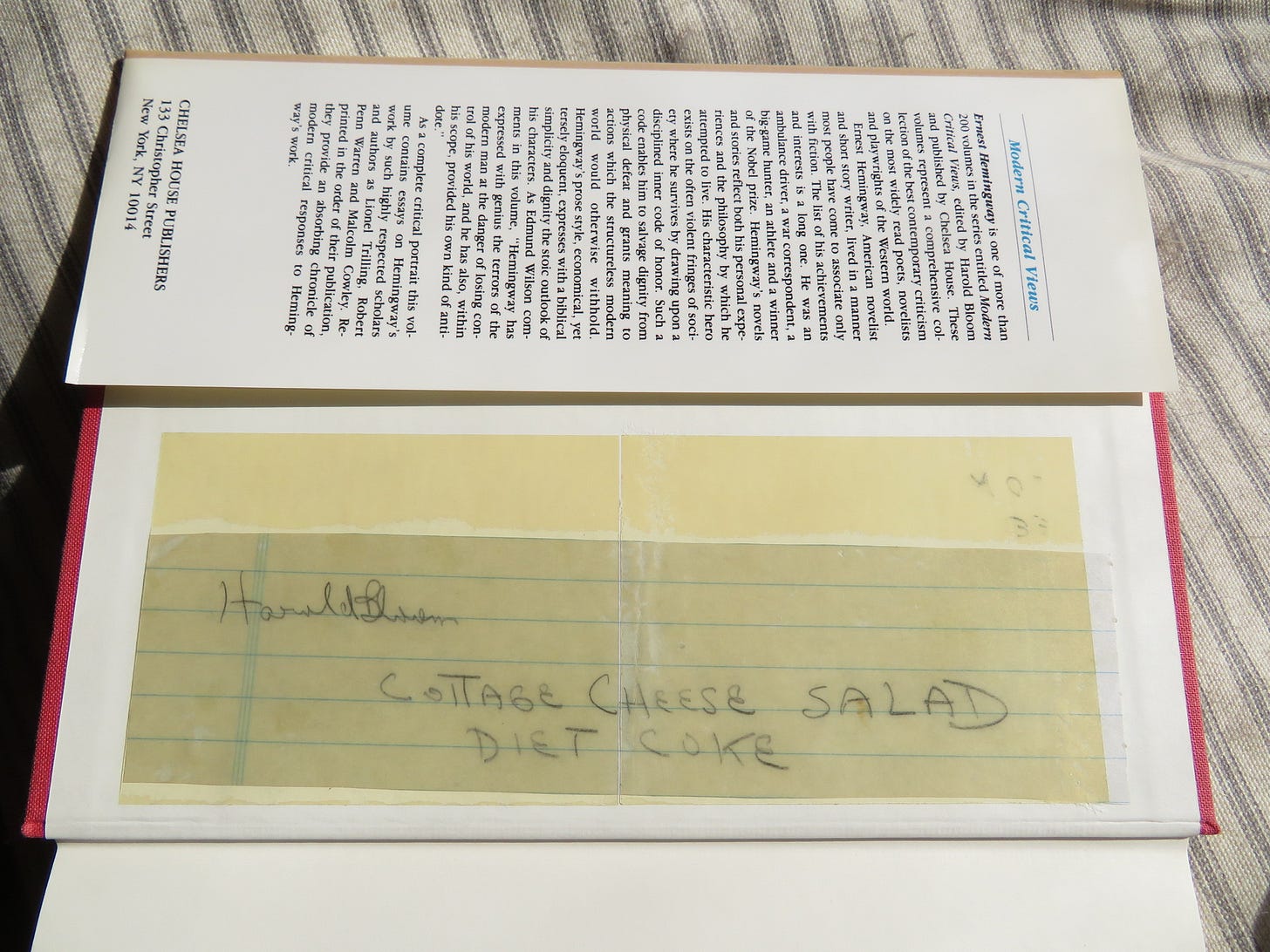

The first time I met the staunch defender of the Western canon and romanticism, he called me “darling,” kissed me on the top of my head, and, shortly thereafter, ordered a cottage cheese salad and diet Coke for lunch, writing it down on a piece of paper. I was so awed at meeting him that I cut out the order and taped it to the inside of his Chelsea House book on Ernest Hemingway, a memento I still have today.

In the introduction, Bloom claims, “The Old Man and the Sea is a tedious allegory, despite its wide popularity, and in time will sink without trace.”

My treasured copy of Harold Bloom’s Chelsea House book on Ernest Hemingway (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

About ten or twelve years after the Chelsea House lunch, my wife and I, on Thanksgiving Day, saw Professor Bloom getting on the same Metro-North train that we were taking at Grand Central. We were going to celebrate with her family in Stamford, Connecticut.

Initially, I found it strange to see the large, disheveled-looking, yet elegant Bronx-born Bloom, the writer of such tomes as The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry, The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, and The Anatomy of Influence: Literature as a Way of Life, wandering alone on the platform, looking for a seat on the train; no one else seemed to recognize one of the most polarizing literary critics of the last several generations. But then I remembered that he was a Yale professor so was probably headed up to New Haven for the holiday, where he would not be by himself.

“[I]n the end, in the end one is alone,” Bloom, who passed away in October 2019 at the age of eighty-nine, wrote. “We are all of us alone. I mean I’m told these days we have to consider ourselves as being in society . . . but in the end one knows one is alone, that one lives at the heart of a solitude.”

My wife tried to stop me from making a beeline to him, saying there was no way he would remember me and to just leave the man be. But, as Mad Transit subscribers know, I can’t help myself.

As I got nearer to him, he saw me and made eye contact. At first I was afraid that he was not thrilled to have been recognized, but he put out his arms and declared, “Darling, how are you?” Then he kissed me on the top of my head.

I am writing this from a hotel in Lumbini, Nepal, the birthplace of the Buddha, who explained, “Be kind. Be thoughtful. Be genuine. But most of all, be thankful.” On Thanksgiving, I will be in Boudha in Kathmandu, visiting with a Nepali family my wife — who is staying in Lumbini for a few more days — and I are close with.

Seven years ago I was in Kathmandu for the second time but had to be called back because of my mother’s illness. She made it through Thanksgiving, her favorite holiday, then passed the next day.

Harold Bloom in 1986 (Bernard Gotfryd Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC)

Tomorrow, I won’t be eating turkey, cottage cheese salad, or even a marlin. I won’t be watching football on television or unbuttoning my pants as I fall on the couch. I won’t be with my brother and sister and their spouses and kids, with my cousins, with my aunt and uncle. I’ll miss my mother and father, both of whom left us too soon.

But I will still be filled with gratitude.

[You can follow Mark Rifkin and This Week in New York every day here.]

Safe travels my friend and Happy Thanksgiving!!

Many blessings to you both! Godspeed.