allying with “the ally“: israel-palestine conflict takes center stage at the public

Asaf Sternheim (Josh Radnor, left) reevaluates his relationship with Israel in Itamar Moses’s The Ally at the Public Theater (photo by Joan Marcus)

Like so many American Jews, I’ve been agonizing over the Israel-Palestine question all my life.

The events of October 7 and the aftermath have left Jews everywhere parsing their words very carefully. In my January 8 Substack post, I wrote, “As a Jew, I feel a responsibility to speak up more now. I don’t want to think twice before wearing my Star of David earring, or putting on my Israel Day baseball cap, or walking into shul on Shabbat or the High Holidays.” But things have gotten only worse since then as Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu continues to bombard Gaza while Hamas refuses to release its hostages.

I have to admit that I’ve had trouble expressing my views about what is happening in Israel; no matter how you feel on the subject, there is someone ready to shout you down, often with debatable facts and numbers.

Then I saw Itamar Moses’s brilliant new play, The Ally, which runs at the Public’s Anspacher Theater through April 7.

The main character, Asaf Sternheim, is a Jewish writer and adjunct professor at an unnamed prestigious American university. Despite serious misgivings, he unwittingly becomes the center point of a brutal sociopolitical battle involving Jewish, Palestinian, and Black students over what is happening in Gaza.

My family visited Israel in November 1977; when we landed, there was one other plane on the tarmac, which had just brought Egyptian president Anwar Sadat to Jerusalem. Sadat addressed the Israeli Knesset about the potential for peace in the Middle East; also present was PLO leader Yasser Arafat.

It was a special time to be in Israel. A year later, Sadat, Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin, and US president Jimmy Carter signed the Camp David Accords. In November 1980, Carter lost his reelection bid to Ronald Reagan. In October 1981, Sadat was assassinated by Egyptian fundamentalists. In October 1983, Begin resigned during the Lebanon War. Arafat was still president and chairman of the PLO when he died in November 2004 of a mysterious blood disorder.

Shortly after Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, I was walking into Grand Central to get on the subway when I found myself amid a pro-Hamas protest.

“Way to support terrorists,” I said to one woman holding up a vitriolic sign.

“Go fuck yourself, asshole,” she cleverly responded.

Patti Smith performs Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War” at Bowery Ballroom (video excerpt by twi-ny/mdr)

At Patti Smith’s Year of the Wood Dragon show at Bowery Ballroom on February 10, Smith, a fervent activist for peace and justice, wore a T-shirt that read, “Hoping for Palestine.” An audience member called out, “I love your shirt, Patti!” Smith didn’t say anything, and neither did I, partly because it wasn’t the place for it but also because I wasn’t sure what to say. I would have been devastated if Smith had started railing against Israel.

I’ve watched the news (both left and right) and read tons of op-eds offering opinions from nearly every possible angle of the conflict. I’ve gotten into discussions with friends and relatives that we had to stop for fear of them becoming too heated.

I’ve recently seen such plays as Prayer for the French Republic, King of the Jews, and Our Class, which focus on antisemitism around the globe.

Through it all, those protesting against Israel insist they are not antisemitic, that their support of the Palestinians — and, too often, Hamas itself — has nothing to do with hatred of Jews.

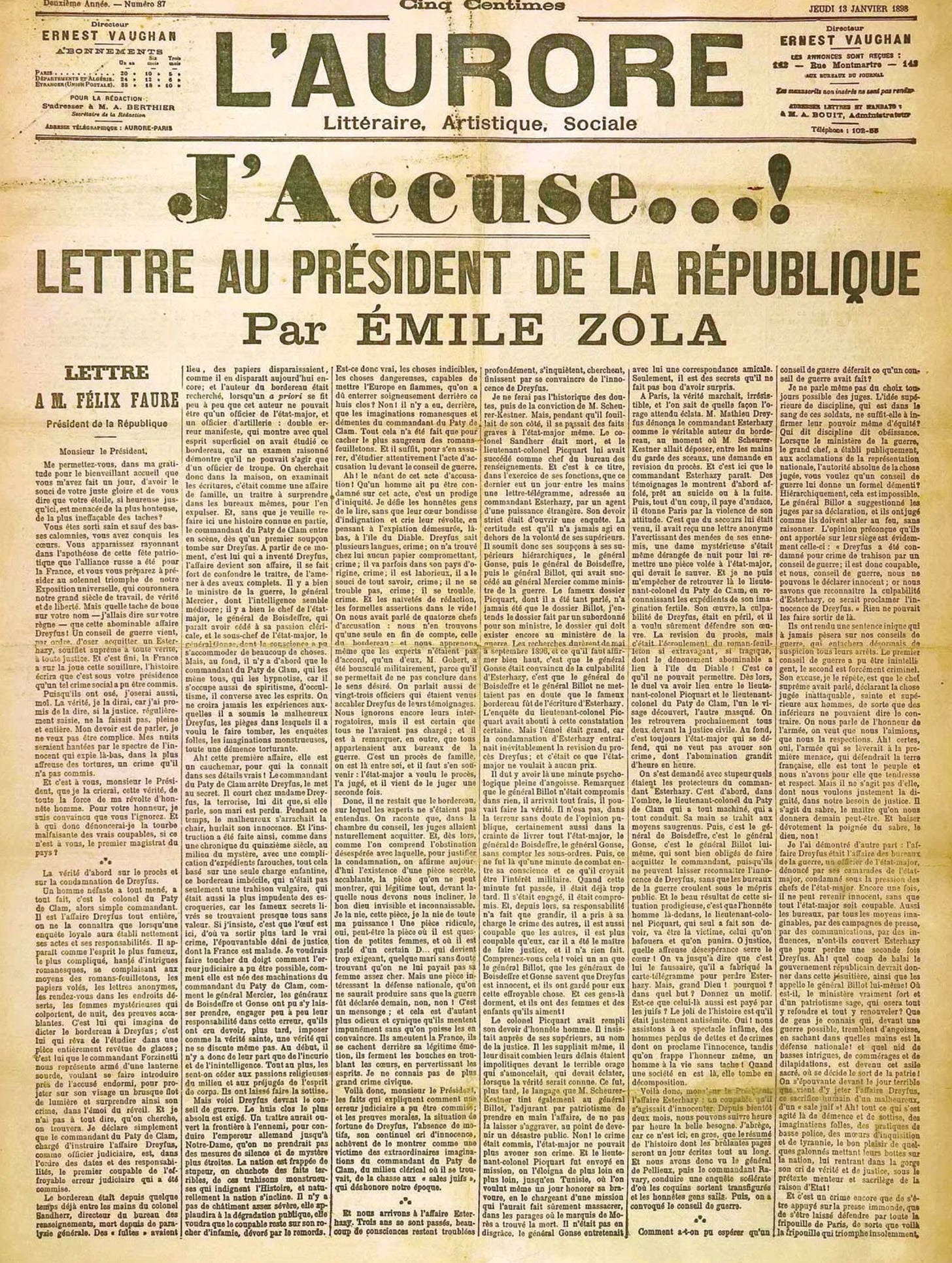

Over the weekend I thought of Émile Zola, who on January 13, 1898, wrote “J’Accuse,” an open letter to French president Félix Faure about the Dreyfus affair, arguing, “It is a crime that those people who wish to see a generous France take her place as leader of all the free and just nations are being accused of fomenting turmoil in the country, denounced by the very plotters who are conniving so shamelessly to foist this miscarriage of justice on the entire world. It is a crime to lie to the public, to twist public opinion to insane lengths in the service of the vilest death-dealing machinations. It is a crime to poison the minds of the meek and the humble, to stoke the passions of reactionism and intolerance, by appealing to that odious antisemitism that, unchecked, will destroy the freedom-loving France of the Rights of Man. It is a crime to exploit patriotism in the service of hatred, and it is, finally, a crime to ensconce the sword as the modern god, whereas all science is toiling to achieve the coming era of truth and justice.”

For speaking out publicly about how French-Jewish artillery officer Capt. Alfred Dreyfus was wrongly convicted of treason and sentenced to life in prison on Devil’s Island, Zola was arrested and convicted of criminal libel and fled to England.

The peace process can be a dangerous game, no matter what side you’re on.

Which brings me back to The Ally.

Like Moses, who won a Tony for his book for the musical The Band’s Visit — about an Egyptian police orchestra that finds itself unexpectedly stuck in a small Israeli town — Asaf’s parents are from Israel and he was raised in Berkeley. Asaf just wants to write his next play and teach his one class, but then he is asked by one of his Black students, Baron Prince (Elijah Jones), to sign a petition regarding the killing of his cousin at the hands of the police.

Asaf decides to bring it home and read it overnight. He then tells his wife, Gwen Kim (Joy Osmanski), about several troubling statements in the twenty-page document, reading them out loud: “The United States must also end all military aid to and impose sanctions on the apartheid state of Israel until it ends the settler-colonialist oppression of the Palestinians through its ongoing occupation of the West Bank, blockade of Gaza, and refusal to recognize any right of return for the refugees of 1948. . . . Failure to do so will leave the United States complicit in the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people.”

Gwen, who is Korean American and the new university administrator for community relations and external affairs, wants Asaf to sign the petition, since it would look bad for her if he didn’t. Despite his misgivings, he does add his name, at least in part because the person behind it all is his ex-girlfriend, Nakia Clark (Cherise Boothe), a well-known Black activist he hasn’t seen in twenty years.

Shortly after his signing goes public, he is asked by the Jewish Rachel Klein (Madeline Weinstein) and the Palestinian Farid El Masry (Michael Khalid Karadsheh) to be the faculty sponsor for a new organization they are starting; their first event will feature a lecture and Q&A by Dr. Isaac Roth, a Jewish intellectual who believes that Israel allows itself to be attacked so it can win wars and steal more land. (It might not be coincidental that Isaac Roth is also the name of a diamond smuggler and Jewish mobster in such video games as Grand Theft Auto IV.)

Against his better judgment, Asaf signs on again, which brings the Jewish Reuven Fisher (Ben Rosenfield) to his office, declaring that Roth is dangerous for Israel and that groups like the one Rachel and Farid are forming will result in yet more antisemitism, and not only on campus.

(Two days after I saw The Ally, a scheduled lecture at Berkeley by Israeli attorney and IDF reservist Ran Bar-Yoshafat on “whether Israel violates international law, the rules of wartime conduct, and how the IDF can better protect civilians” was shut down when the campus group Bears for Palestine led about two hundred protesters storming the event, resulting in Bar-Yoshafat and Jewish students having to flee through an underground tunnel as the mob chanted, “Intifada! Intifada!”)

“I mean, I’m not . . . that Jewish,” Asaf says at one point, befuddled that he has been dragged into this ever-expanding clash.

Asaf Sternheim (Josh Radnor) finds himself on the hot seat in The Ally (photo by Joan Marcus)

For most of the second act, Asaf, sensationally portrayed by Josh Radnor, who is Jewish (and has just released the album Eulogy), is surrounded by Rachel, Farid, Nakia, and Baron, who lash out at him, but he refuses to give in; every time it appears that he is too frustrated and beaten, he gets back up and throws critical issues at them. Like me and so many other American Jews, he supports the existence of the State of Israel but doesn’t always agree with the policies of its leaders. He disputes such words as “apartheid” and “genocide” but knows that Israel has to do better when it comes to its treatment of the Arab population.

Explaining how complex the situation is, he says, “Thank you, all, seriously, this is useful, this is clarifying. It’s why it’s good to talk about this stuff, right? I’m saying it’s two things. It’s both. Israel is two different things. One is a regional power, backed by Western interests, occupying territory beyond its borders it should return. The other . . . is a haven. For a globally persecuted minority, on their ancestral land — not just theirs, but also theirs. And the second thing, yeah, complicates the first because while, say, leaving the West Bank is the moral choice, there is a question of security.”

But the others see it only as good vs. evil, with Israel forever the bad guy.

Oh, by the way, did I mention that the play unfolds in the fall of 2023, before October 7?

The 160-minute play (including intermission) is directed by Lila Neugebauer (Appropriate, The Wolves) with an unrelenting fierceness — and surprising doses of humor — on Lael Jellinek’s sparse set, consisting of academic wood paneling and a few chairs. When Asaf sits in one alone in the middle of the room, being verbally harassed by the others, it’s like Dreyfus or Zola in the witness stand with no chance of winning but never giving up the fight. The diverse cast is excellent, but it’s Radnor’s (Disgraced, How I Met Your Mother) show.

I have to admit that after Farid gave an impassioned, angry speech about his family’s history in Palestine, I seriously considered walking out, something I never do, because I thought that Farid was speaking for Moses (Bach at Leipzig, Outrage), that this was going to be the takeaway, an anti-Israel, anti-Jewish resolution.

I’m glad I stayed, just like Asaf; I was riveted by his every word, his every gesture. He was speaking for me, as if reading my mind, but far more eloquently.

He was also speaking for me when he said, “I’m afraid of how they hate us. And of our fear turning us into the very thing they hate.”

Sounds like a powerful play, but more immediately I was taken with your own impressions--which run the gamut, as do mine (to say the least).

Mark, thanks for writing about the play, but more importantly for sharing and talking about the complexities of Israel and the Palestinian people. May all have the conditions of peace.